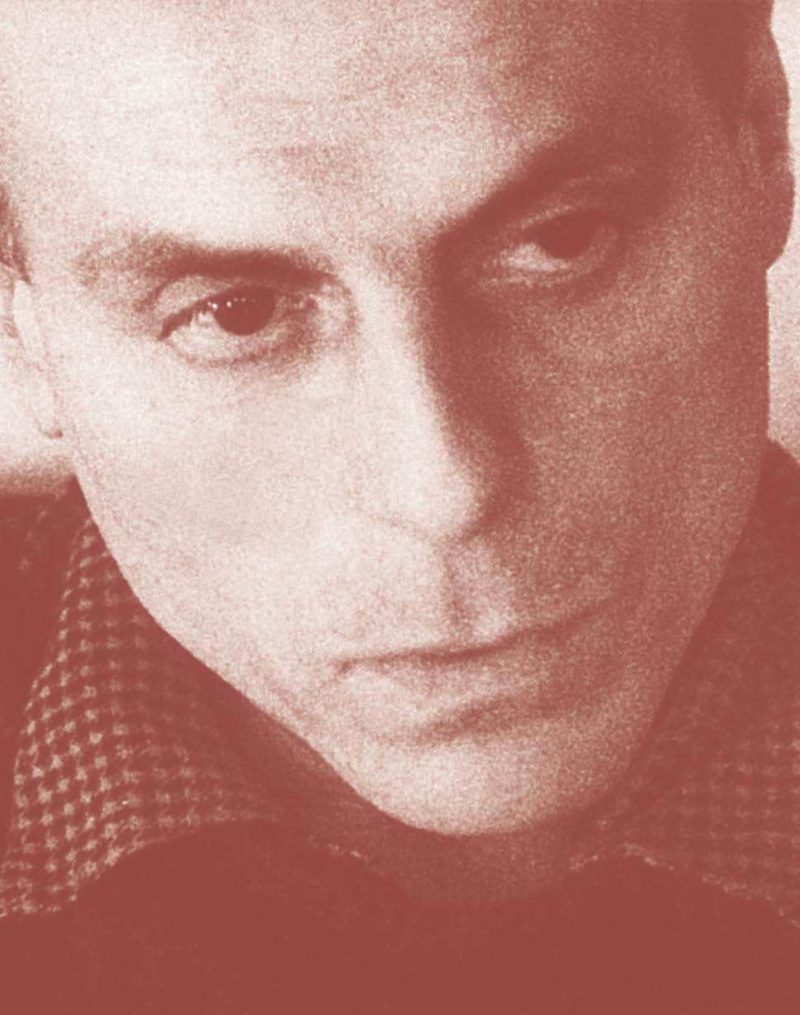

GHÉRASIM LUCA

From these three writers, Ghérasim Luca was the only one to have pushed the notion of liberty very far, to the point of constant reinvention and dismantling any social and physiological ‘laws’ (such as the Oedip Complex) that keep human beings static. In the Dialectic of the Dialectics, written with Dolfi Trost, he argues that established art movements, especially surrealism at that time, inevitably fall into mannerism, whose practice becomes historically classified and politically instrumentalized. One can reach a sort of ‘freedom’ by

“leading his life in a constant state of revolution, which can be maintained through a permanent state of negating the negation towards everything and everybody. You are your own twin”.

But these are just ideas that are somewhat hard to grasp in practice. How are we going to escape without ‘getting out’? Raoul Sangla’s film Comment s’en sortir sans sortir perfectly depicts it. Here, we see Ghérasim Luca reciting

Ma Déraison D’Être, Auto-Détermination, Le Tangage De Ma Langue, Héros-Limite, Quart D’Heure De Culture Métaphysique, Le Verbe, Prendre Corps and Passionnément.

As in any performance, the body plays a crucial role, as it enables communication. The voice confirms the thought and its gesture. The poet feels the words sprouting through a tube full of obstacles and constraints. He trembles, huddles and expands in a blank surrounding.

His neck, chin and mouth move back and forth, struggling to utter abbreviated words. His head is bald. His black outfit on a white background resembles the letters that move on a sheet of paper. The organic act of writing and reciting translate each other. A body that reconfigures inside its contour, expanding it until its own death.

“Pour le rite de la mort des mots

j’écris mes cris mes

rires pires que fous: faux

et mon éthique phonétique

je la jette comme un sort sur le langage.”

French is Luca’s adopted language, appropriated it in a unique way. The accents are shifted at the end of the words, creating a non-French cadence, by taking it out of its own system. Not only did he make the language ‘move’ by playing with all the elements of speech-sounds, letters, syllablesand words, but he also redesigned it. All this is sprinkled with codes and associations that resonate with his ideas and theories.

“Je suis hélas! donc on me pense.”

“Comme le «doux» dans le doute suis-je le «son» de mes songes?”

By negating the negation of French language, he restores life within it without attaching to it.

“Oublie ta langue maternelle

sois étranger à la langue d’adoption étrangère

seule

la

no man’s langue.”

Through stammering, he didn’t estrange himself form eroticism and love. In the film’s last two poems Prendre corps and Passionnément everything culminates in

“t’aime je t’aime passionnément je t’ai je t’aime passionné né je t’aime passionné je t’aime passionnément je t’aime je t’aime passio passionnément

...which the audience’s body will shout and the poet will be relieved.