Karkhana

Niels Latomme

The festival claims to highlight the parallells and the mutual influence between Western Avant-Garde music and Non-Western music. We see that both share a common interest in the notion of transcentendalism. As being raised in an Arabic country, how do you feel about this?

Mazen Kerbay

I definitely feel the big influence of Western music on the Arabic world. On a personal level I’m influenced by the Middle-East. However, as a musician my first influence was the free jazz of John Coltrane, Evan Parker and Peter Brötzmann. So I don’t feel the direct influence of Arabic music, because I don’t play and never intended to play Arabic music — it’s like asking Evan Parker what the influence of British Folk music on his music. But I recognize the Arabic context has an influence on who I am, as a human being first and as a musician. Arabic music has been around me all my live, sometimes I hated it when my parents put it on for instance. I would define myself as an Arab playing Western avant-garde music, and in it lies a paradox — my thinking blends two opposite forces: being an Arab, influenced by Western music, and I don’t understand it myself completely. But this is not so uncommon: John Coltrane used oriental modes and appropriated them, although he is still playing free jazz, not Arabic music.

NL

Is transcendentalism something important for you as a musician?

MK

It’s very important, especially in improvisation. I like this idea of music which isn’t rooted anymore. You feel of course that Afro-American free jazz is rooted in the black community, but the great thing about improvisation music, is that you can adopt the language everywhere. I could play with one Japanese drummer or with an Indonesian musician, and although we never have met, each of us can come with his highly personal language, and share this. This music works as an international language, cause improv music got rid of the idea that the basis of music should be conventional structures and aspects of music, like rhythm, modes and harmony. This makes the music open, which is great.

I’ve been reluctant to define myself as an Lebanese artist. My work should be judged against the history of music, and not against my background and the context I’ve been born in. It’s very diminishing to be classified as an Arab or Lebanese musician, for any music or musician. You don’t say Picasso is a Spanish artist, he’s in the first place an artist. Of course I could define (and sell) myself as the head of the Lebanese avant-garde — which Sharif and I are, in a way —, but it’s too easy to do something not so great, but being looked upon as great because you were the first in this or that context. So it’s very difficult and dangerous to delve into this, as an artist you have to be aware of your influences, and be aware that you just move a small stone in the giant river which the history of music is. You are challenging the whole music, not the avant-garde in Lebanon. It’s easy to be the best in something, if you are the only one.

NL

It’s more about the individual expression for you?

MK

Totally, even there is a community, which we are pushing with a festival and it makes me happy to see the scene is growing in Lebanon. Still, if your are coming from by instance Ethiopia, or Lebanon, people seem to be surprised by the idea that there is avant-garde in Ethiopia or Lebanon. Of course there is, it is as hard to find out about Evan Parker in New York than in Beirut. Where you are, you always have to be curious and to dig to find out about experimental stuff.

NL

You realize that the idea of an avant-garde or experimental artist, expressing an highly individual language is a very Western idea — if you look into the history of art?

MK

Maybe, mostly European avant-garde and experimental musicians tend to. More than americans. There are many European things influencing me, maybe this is one of them — I never thought of this like that.

Although, if you look to one of my biggest references — John Coltrane, always —, the Americans have a very mystical way of seeing music, and take it as something for the community. That’s where Black Spiritual Jazz came from, music for the people, to dance on. Where Peter Brötzmann, together with a lot of the Europeans, claim the complete opposite — it’s art for the art. Brötzmann called even one of his albums ‘fuck the world’. In Europe the communal idea has completely disappeared.

This highly individual and European approach influenced me. My background is in any way very European, also in literature — the fact that I speak French since I was very young, it gives me a very European point to look at things. Although, as a human I am less individualistic than Europeans. I still have this Lebanese background in which family and the community is taking a very important part of life. I cannot say why those things are like that, I can point out how I arrived here, but not why. I’m even not interested in knowing, the most important thing is to do the work.

NL

Maybe you could say that the European fascination for the Middle-East, the Other and the Exotic makes the West forget how close the Middle-East is, and how less we differ. We have a shared history.

MK

Totally, there is not at all a sharp distinction between the West and The Middle-East. That’s the main reason why I don’t want to define me as an Lebanese artist. I fight against this Orientalism. It’s not easy, because if I talk in my first book about the war, it’s easier to got it published than when I would have talked about spring. The West expect us to talk about this, although you don’t expect a German to talk about the Holocaust. Even when you are not speaking about it, people tend to look for it. If a make this helicopter like sounds with my trumpet, people tell me it reminds them of the war, but if European players make the same sort of sounds, people hear something else — a dentist, or a workshop. In the mind of the receiver, there is already something twisted. I don’t say this a bad or good thing, but it’s a fact. When you are coming from this or that region, people interpret the music based on that knowledge.

NL

That’s what I am actually doing right now, right?

MK

Yes.

NL

Let’s talk about the music than! Tell me where Karkanha comes from and how does the band relates to Orchestre Omar?

MK

Well, Orchestre Omar started out as an all guitarist band. Since all those people, from Turkey, Canada and Egypt were here in Beirut, it was a great opportunity to do another group. We liked this Middle-Eastern connection, because for us it always has been very difficult to find other people playing this music in this region. When we discovered that in Istanbul is a vivid improv scene, we were very happy to meet them. Of course there is a scene in Istanbul, but if you look to Syria, Palestine, to Morocco, there is no scene for this music. So we were happy to find these like minded people so close.

Karkahna is totally improv, if you compare it to Orchestre Omar, which is more composed. We played a gig which was recorded and led to the record.

Funnily enough, without talking about it, the sound went towards this oriental, middle eastern edge by the instrumentation. Although is totally experimental and avant-garde (I don’t like to say avant-garde, because after doing this for 15 years, you cannot call it avant-garde anymore, I think), because we don’t use for instance arab modes. We don’t have an agenda in this, the outcome sounded oriental, but we are no extremists, so we didn’t think this was bad.

NL

If you look at one of you’re great inspirations, John Coltrane, of like minded people as the Art Ensemble of Chicago, the were very aware about identity and about constructing a new identity for Afro-Americans. Is this something which keeps you busy?

MK

I don’t think about this, because I work very instinctively. I don’t have an agenda. In this I’m maybe very Western, very centered on my own work and very individualistic.

It’s war I don’t have to fight, because I don’t live as a third generation Lebanese in bad conditions in for instance Germany. So I don’t have to bring back and construct a new identity for myself. I chose to being influenced by the Western culture, it was never forced upon me. On the contrary, it actually opened the world for me, without jeopardizing my own world. In way, you could say I think about not being seen as an Arab artist, but just as a musician.

NL

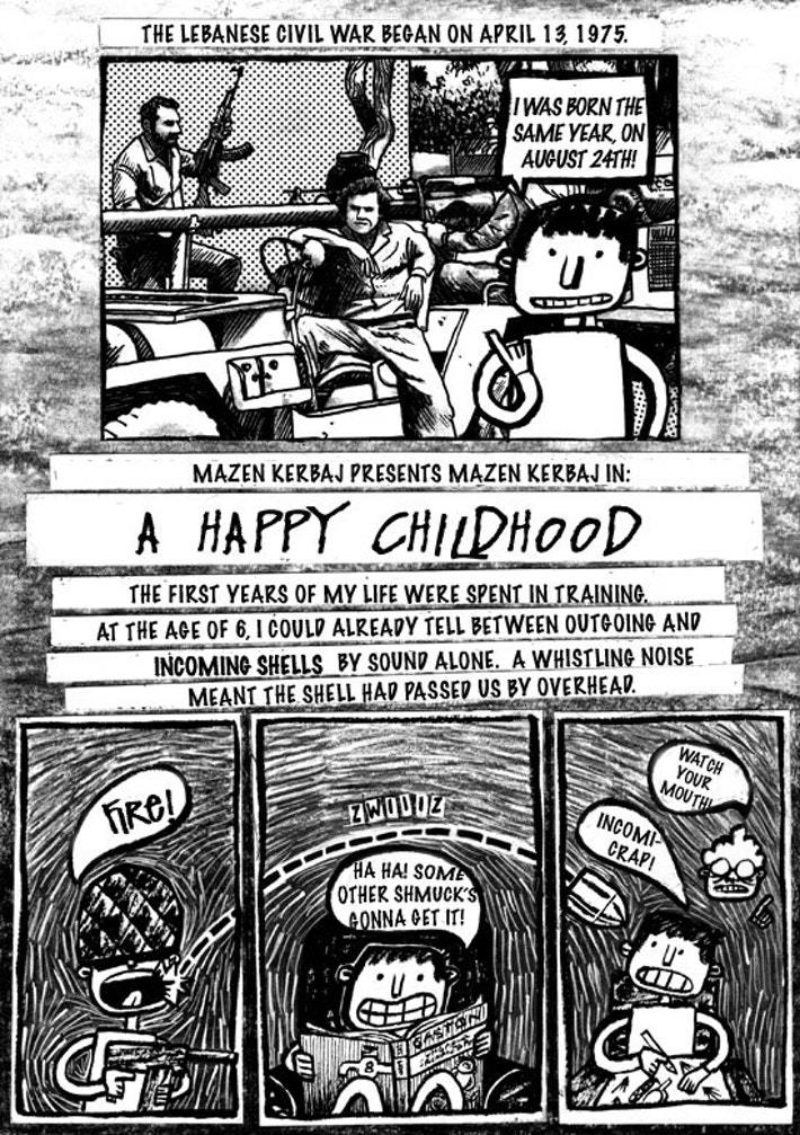

You are also a comic artist, and it seems that you have a completely different approach towards that art than towards music, which aims towards a radical improvisation?

MK

I see both arts as something completely different, without any priority for one of them. Drawing comics is something very personal and introvert, which I do alone. When I finish a book and it comes out, it’s actually dead for me. It’s my past, which becomes the present for the reader. While music is something which lives on the moment I’m doing it for an audience. It’s much more direct, talking directly to the audience. At least, I always thought they were completely opposed things for my.

But, when I started to talk extensively about both aspects of my art, it occurred to me that there are more similarities then I would admit. For a book, I never work with a proper scenario, stories develop like improvisation in music. It was always very loose. Recently I even developed a simple technique to draw live, like I play music — in combination with music by Sharif —, I draw things, it’s projected and at the end they are gone. I actually took me years to get to this.

Also in my music, I also want to start working on pieces with overdubs and work towards a finished product — like a book. So the things are not so opposite as I first thought.

The last thing which is similar, is that I don’t refuse humor in my music. It’s not that I make jokes while playing, and I am very serious about my music. But when it makes people laugh, it’s beautiful I think. I think it’s very hard to make someone laugh, much harder than to make someone cry. It a thing that differentiate us.

NL

Why did you choose for the trumpet?

MK

Actually that is a very funny story in itself. It’s Sharif’s fault. When we were young, we had this big group of friends with whom we came together to have fun, smoke hasjiesh and listen to music. Me and Sharif were always the last staying up till 6 in the morning listening to music. Mostly good rock, kraut rock and stuff like that. When Sharif moved to France, he admitted to me that he started listening to jazz — my response was, ‘Sharif, jazz is for old people’. But he kept on repeating I should listen to John Coltrane. One day I found the Atlantic records by Coltrane, with this beautiful piece with Eric Dolphy on the flute, which hooked me. Sharif started to bring me cd’s by Coltrane and others out of France. That’s how I got to improv and free jazz.

To that point, I was 18, I never played music. I was already sure to be a comic artist. Sharif was more passioned by music. On day he was sitting at my place and told me that he got this trumpet as a present, but didn’t do anything with it. He offered it to me, and that’s where I started as a musician, like a joke actually.

At first we were with 8 friends doing so-called free jazz, but it was shitty music. But I kept on playing with Sharif, and his wife Christine, who played saxophone. And little by little, the others fell off. One day we were playing, and my ex-wife came in the room and asked us which cd we were listening to. It occurred then to me that I really got into something, and that it became real and serious. I was surprised myself.

NL

It’s interesting to hear you telling this. Last year I realized, something in common between experimental music and ethnic music seems to be that they are born out of little peer to peer communities. In little villages, or in small groups of friends, like yours. It seems that these isolated groups are a great soil to grow new music on it?

MK

Totally, we were isolated, I’m talking pre-internet. This music wasn’t easy to find. At that moment we never dreamt that what we were doing would be appreciated. While nowadays after 15 years this festival and the audience for improv is still growing in Lebanon. And it’s young people coming to this festivals, not old free jazz fans, like in Europe. For long I seemed to be the only one playing free music in Lebanon, and a lot of people told me that I should focus on what I was talented in — in comics —, not in this shit music. But one day, someone came to this cd-shop where I worked, he asked me to play together. Which was unbelieveable. We formed then the A Trio, which still goes on. And it grows and grows.

NL

A last question: did the war put an urgency in Lebanese free music, if you compare it to European music? I ask this, not because of my interest of the consequences of the war, but because I have the impression that there is a vitality missing in the West, because it doesn’t need new forms.

MK

Well, I don’t like to talk too much about this. Because, it’s the same with being a Lebanese, that being defined it creates this context for my music. But as a kid, I accepted the war, and its sounds as something normal. I didn’t thought about it that much, and I didn’t felt traumatized, it felt natural. It was later that I questioned it, when I became 25. The Wire did once an interview with me, and they put this on top ‘War Child Mazer Kerbay’, which I hated, because I only talked for 2 minutes about this experience. So I’m always reluctant to talk about this.

But It was later that something changed with the 33 day war in 2006. After the war in the 70ties, Lebanon became a cultural wasteland. While in the 60ties Beirut was a the cultural capital in the Middle East. There was a blossoming art, poetry and proze scene. For instance, one year after the premiere of Ionesco in Paris, it was performed in Arab in Beirut. Except, funnily, for music — even thought Stockhausen performed his pieces in Beirut.

After the war, our generation had a craving for new things. All the known artists from Beirut – the good ones and the bad ones – are from this generation. The audience is still craving for something new. I always found it fascinating how my parents, who were both artists, kept on creating during the war. And I wondered how I would react as an artist during wartime. Sadly this question was answered during the 33 day war, in which I never felt so creative. So what you feel about the West, makes totally sense to me. It’s sad to say that peace is not good for art. A war causes this vitality, and this urge to create a new world and new forms. It’s bad for people, but good for art.