Philip Corner

It all started in 1990 in Argentina, when I saw a small catalogue printed by Frog Peak composers’ collective. I was looking for experimental music from different, alternative resources due to the usual lack of information on these matters in South America. Many musicians and composers from the American Experimental tradition dealing with post-Cagean, minimalism, unusual sound resources, idiosyncratic electronic music and instructional scores were present in such a catalogue. But immediately some short descriptions on Philip Corner’s work took my attention in a way that triggered my curiosity, beyond my more conventional focus on Cage and New York School music that I began appreciating in my adolescent years. I’ve started my searching for minimalism and extreme experimental forms of music since early eighties and I felt from the beginning that Corner represent a true one-of-a-kind personality in the world of post-Cagean aesthetics. Soon I discovered that Corner’s work implied a varied spectrum of languages using all kind of sound resources, graphic scores, ecology, spirituality, performance and intermedia, even as a visual artist many times labeled as a plain “Fluxus artist.” A myriad of documents on him has been published in all sorts of media, books, catalogues and magazines throughout the years. With a music career which began in the ‘50’s, his first recordings commercially available in the mid-70s. Fortunately, since the late nineties, many documents of his music have been released, thanks to many small labels in Europe and (to a lesser extent) the United States.

After devouring papers and years of collecting materials on him, I thought that it was curious that nobody in USA or Europe was interested in writing an entire book on this complex and fascinating creative personality and work. For many reasons, I decided to start with this task, trying to compile information and my own comments and descriptions of some of his extremely wide body of work. I was very fortunate in the process, thanks to the kind generosity and interest of Philip Corner himself and also from his wife – choreographer and dancer Phoebe Neville. Both helped me a lot in my travels to Italy, visiting them and asking a lot of things and digging passionately into their impressive archives, with plenty of documents from the most radical years in the history of art (as well as doing long hours of telephone conversations overseas). This book project was warmly received and supported in Buenos Aires by a new publishing imprint, Templo en el Oído (the name comes from first “Sonnet to Orpheus” by Rainer Maria Rilke) and is being prepared to see the light of day in late 2013. First, it will be published in Spanish but I hope other people would be curious about the work in other languages too. I would be very happy to contribute in some manner to a wider appreciation on the work by one of the most remarkable composers of experimental music.

Philip Corner was born in 1933 in the Bronx and has lived in Italy since 1992. He is both a composer and an artist who has created multifarious works in a variety of contexts throughout his life. From the post-Cage sound-related musical compositions to his interpretations for piano, trombone, alphorn and gamelan, as well as his performance in Fluxus activities since the early sixties, Corner has been working towards achieving unity among his different creative periods, in which the most radical avant-garde expressions and a respect for art history (and its knowledge) blend in a most peculiar dialogue. In view of his diverse work and extensive catalogue, Corner has organized his own chronology by creative periods during which he has tackled different themes and whose gradual interweaving constitutes what he has called Lifework1, a unity blending everyday life, his creative activity and the constant flow between thinking and the sensitive realm. For over fifty years, Corner has combined concepts of highly formal abstraction with purely poetic moments expressed through such dissimilar means as calligraphy or a sonorous outdoor ride. His works comprise written scores or ‘pieces of reality’ such as stones, paper or shapes found in nature, which can be experienced either as a visual stimulus, a conversion to sound or an enigmatic shape drawn on a piece of paper.

Culture (Tradition, Assimilation) 1950 – 1959

He got his bachelor degree in music in the New York City College in 1955 and his Master of Arts degree in 1959, after having studied with Henry Cowell and Otto Luening at the Columbia University. From 1955 to 1957, he attended Olivier Messiaen’s analysis lessons at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique. A study of the names will illustrate the context. An experimentalist such as Cowell --open to non-Western sounds besides being the creator of the cluster sound in the piano literature-- made an impact on a young Corner, who would in turn attend the classes of (formalist) electronic music pioneer Otto Luening and who would be indelibly influenced by Messiaen 2. Philip Corner’s later mobilization to South Korea to serve in the Army, between 1959 and 1960, put him in touch with the music and culture of that remote place, thus providing him with a different experience which would mark his whole subsequent creative life: his study of calligraphy with the local teacher Ki-sung Kim, the very man who would re-christen him with as poetic a name as it would become premonitory: Gwan Pok. This Korean expression is translatable as “contemplating waterfall,” a condition that Corner would revisit many years later through different experiences of conceptual music, like his remarkable “Ear Journeys: Water.”

During this period, Corner noticeably put emphasis on those means that he felt close to. The piano sheet music from his first period includes twelve-tone pieces, as well as others which refer back to classical forms from his catalog (preludes and fugues, a fantasy, a scherzo for wind instruments and a rondeau for trombone). His “Etincelles” (sparks) for piano is one of the first examples of repetitive music -- minimalist perhaps-- including dissonant elements whose variation lies in the strict indication of nuances for each note.3 In “Homage to Couperin,” for clavichord and tape with sounds and noises, he makes reference to the French Baroque master, whose work Corner combined with an unconventional sense of electronic music.

The World (Graphic Innovations and Indeterminacy) 1960-1975

Back from Korea, Corner resumed his activity in California and moved to New York soon afterwards, where he would develop increasingly experimental work. Two milestones undoubtedly marked this period: the foundation of the Tone Roads Chamber Ensemble and his participation as in-residence composer and performer of the Judson Dance Theater. The name ‘Tone Roads’ came from two compositions written by Charles Ives for chamber orchestra. This group was made up of two other young colleagues and friends of Corner’s who would eventually become outstanding figures within the experimental music scene: violinist Malcolm Goldstein and the pianist James Tenney, both of them composers also. The idea behind Tone Roads was to take as a starting point American experimentalist masters --Ruggles and Cowell, the expatriate composer Varèse --and the great international avant-garde represented by Messiaen or Webern. Corner would acknowledge the merits of the past while opening new paths towards a promising future. To his interest in Satie, Corner added his contact with Earle Brown (at the height of his mobile forms) and topless cellist Charlotte Moorman who played Nam June Paik’s “TV cello”4.

It was during the Judson Dance Theatre period that Corner gave free rein to his own ideas within a field of open experimentation and form innovation. Corner added fresh air into the post-Cage world concepts through a series of indeterminate scores, diverse graphic forms, tape music and a varied degree of indeterminacy. His 3-volume From the Judson Days5 records cover the 1961-1965 period, although other pieces span back to some earlier years Works made within the most radical pursuit of a new sound (and social) world and the pre-historical division between New York musical pieces and districts: towards the North, the world close to the powerful institutions (Columbia, Juilliard); heading South, a concrete jungle with (in those days) poor apartments and lofts serving as improvised theatres which sheltered the boldest artistic dreams. The Judson period gave Corner a leading role in one of the most productive moments of avant-garde art, when the Living Theatre experiences would blend with the onset of postmodern dance, which would go far beyond Graham’s and Cunningham’s models by adding movements from everyday life and which would be in line with the advent of the most extreme minimalism. It will suffice to give but a few examples of that time: Lucinda Pastime is a piece of Corner’s made for choreographer Lucinda Childs by using a tape recorder to capture sounds from different kitchen tools hitting against the sink; “Oracle, a Cantata on Images of War” --which was requested by the Living Theatre-- included all kinds of explosions caused by microphone plug saturation and implied a clear anti-war plea in the midst of the Vietnam War.

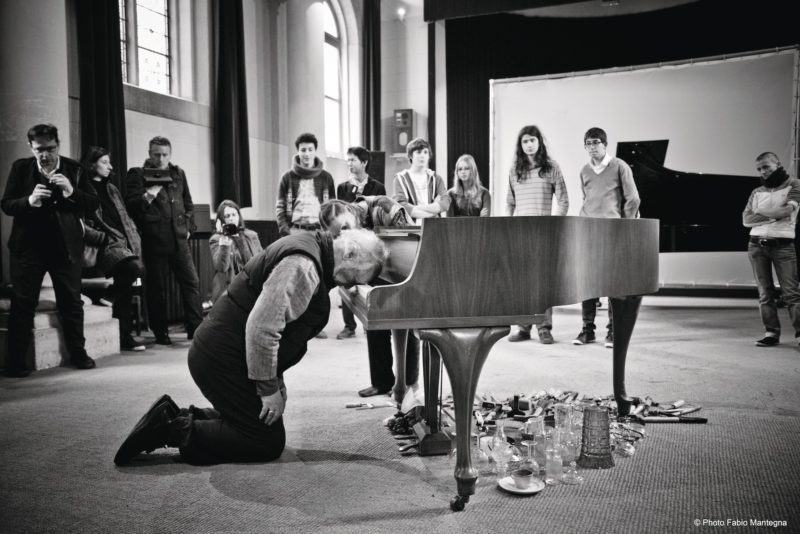

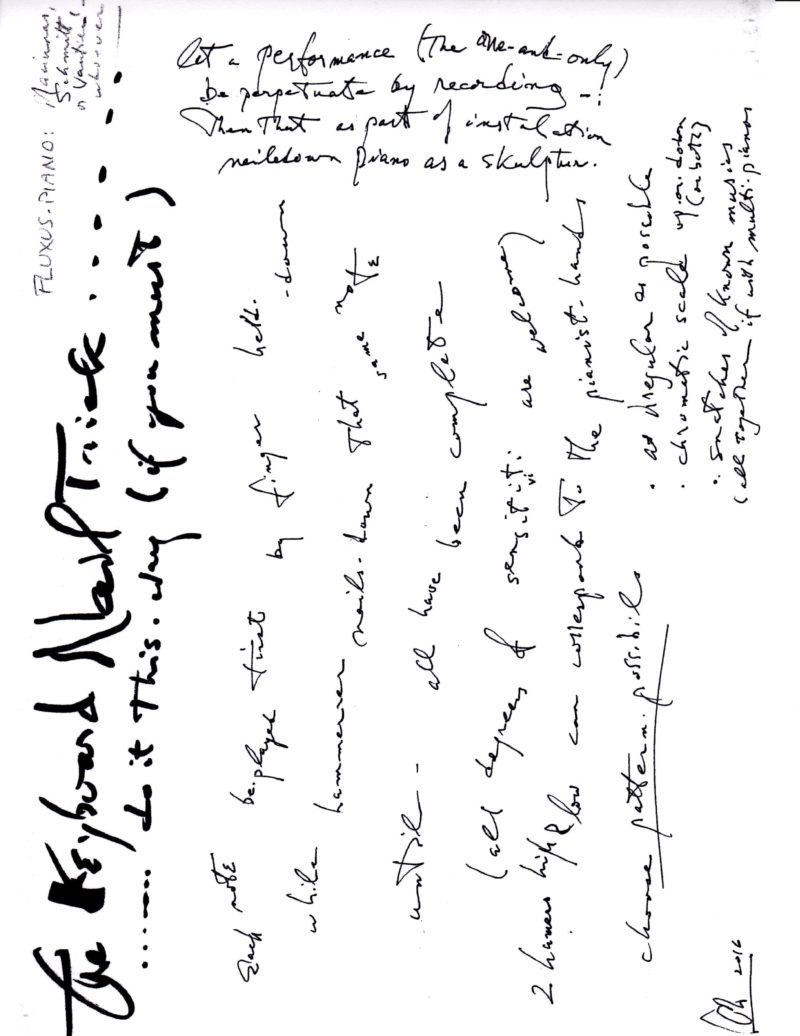

On top of that, there is another key element in Corner’s early sixties stage. The use of musical notation with instructions and the incorporation of actions stemming from a more immediate and zen-like sense of happening made Corner also became a foundation of the Fluxus movement. Since its beginnings, the friendship between Corner, Alison Knowles and Dick Higgins resulted in a dialogue that has continued onto the present, even after Higgins’ death. Corner would also play a key role in conceiving the elements that of an expressive protominimalism --he himself would remember that Young objected to his unisons with crescendo 6: he combined them with the poetical addition of various actions. Without actually attending it, Corner took part in the Fluxus Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik held in Wiesbaden in 1962. George Maciunas, Dick Higgins, Alison Knowles, Wolf Vostell, Benjamin Patterson and Emmett Williams presented their ‘Piano Activities,’ which caused the biggest scandal of the festival – throughout the concert by destroying a piano whose pieces were auctioned among the attendants.

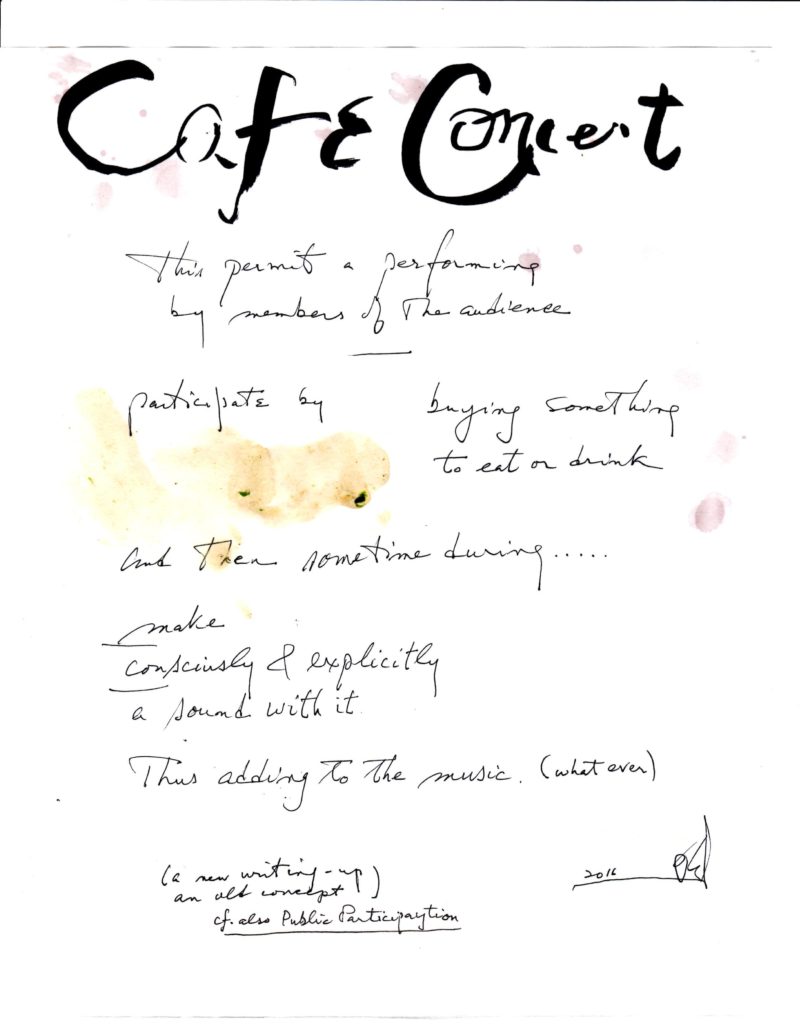

In connection with the Fluxus movement, we have his CarrotChewPerformance, an unusual event consisting in a carrot-chewing activity, as well as a series of conceptual works through which he has exhibited his vision of minimalism before this movement came to be known as such. “OM Emerging” is part of his series of sound-mantra-based works and it is intended for sustained-note instruments as well as his “Metal Meditations” series, which includes all kinds of explorations on the sounds of resonant metal, like “Gong!” Corner’s untiring experimentation during this period became increasingly interdisciplinary, as shown by his pieces written as open instructions in the format known as ‘prose music.’ The sound sources can be derived from all kinds of instruments, dance activities, magnetophone tapes and the special field of action music, which is connected with performance art.

Mind (instruction pages with examples; precisions added to freedom) 1972 – 1989.

It is in 1972 that Corner co-founded Sounds out from Silent Spaces with his then wife, astrologist and medium Julie Winter. This workshop fostered the contemplation of sounds in nature without too many preconceived plans and focused on the ability to have open ears to both the surrounding world and the inner being. With some common points with Cage’s sound world (and eventually with Pauline Oliveros’ Deep Listening principles) together with its own nuances, the workshop meetings continued until 1979. The other milestone of this period is a deepening of knowledge about the gamelan, which Corner would show through his ‘Gamelan Series’ --around five hundred pieces featuring varied levels of determinacy, in which he developed a somewhat poetic but mostly rigorously constructed writing, almost likened to poetic algorithms where each decision stage leads to new paths of sonorous options. These pieces could be interpreted on traditional gamelan instruments, while appealing to a sense of form resulting from minimalist repetitionism, as well as from various strategies of open and random music. Corner’s idea did not consist in repeating his own framework of “hard” musicological research, but in the possibility of expanding his ideas about resonant music, the use of metals and a strong concentration capacity, together with a meditative context derived from his interest in diverse forms of Oriental traditions, without neglecting intuitive, metaphysical or sensitive aspects7. The series also includes scores with open instrumentation or other scores clearly intended for piano, perhaps providing a new outlook of the new ideas resulting from the old research by Canadian composer Colin McPhee during the ‘30’s. He found a vehicle for the gamelan experience in his partnership with composer and ethnomusicologist Barbara Benary and composer Daniel Goode, who are co-founders of the Gamelan Son of Lion ensemble in 1976 and, to some extent, pioneers of the currently widespread movement of new music for gamelan8. Within a more conceptual field, Corner deepened his strategy of music scores with instructions and intermedia pieces, in which it would be more difficult to set the limits between calligraphy, drawing, facilities or existential environment. His “Petali Pianissimo” include flower petals between the piano strings; “Peace, Be Still” is a round with word repetitions like those in a soft prayer; “Orgasms’ are colourful aquarelas; and ‘Some Silences’ is a wide collection of suggestions for silent experimentation.

Body (Breakthrough to Conscious Spontaneity) 1989 – 1999

Pieces like “Passages from the material to the spiritual, and back” deal with a new living experience stage. Verbal Fluxus-like pieces expand into new territories. The old Judson Dance Theater experiences become workshops aimed at groups of dancers or people interested in body expression, such as the De Winter Course in Amsterdam, where ideas-compositions like “Gong/Ear,” “One Note Once,” “Music Silences and Gesture Stillness” would be combined --all of them sonorous-meditative spaces in which sound corporality and profound listening would outshine sound itself as a timbre or acoustic construction9. It was in those years that Corner made an important decision. He left behind his teaching career at Rutgers University in Nueva Jersey and decides to move to Italy, where he settles down in Reggio Emilia in 1992 with his current wife, dancer Phoebe Neville. After shipping his books and manuscripts --and becoming aware of “the weight of knowledge”-- Corner reaches Italy in the pursuit of more adequate venues to present his works. At the same time, he starts a stage of lonely exploration of the sounds produced by the alphorn, an instrument easily adjustable to his trombone knowledge. The alphorn is endowed with an ancestral character consisting in continuous sounds and harmonic listening, and it allows expanded techniques such as simultaneous singing and playing. The kinship between the alphorn and the Tibetan trumpet or the didgeridoo features continuity, introspection and a concentrated touch to toy with harmonic sounds as common characteristics. For many years, Corner called such experiences ‘Earth Breath’ and took his instrument to clearings in the woods, both in the vicinity of the Alps and in the backyard of his own house, where the privacy is revealed in some recordings through bird singing and car noises from the adjacent street10. Likewise, the sound-life experience as daily meditation resumed in the exploration of metal sonority in other moments. Korean shaman cymbals are Corner’s favourite to obtain a sound consisting in different tap, times and nuances (these cymbals have a less resonant sound, more like “metal sheets,” than other similar instruments of Chinese origin, for example) 11.

Pieces such as “Modern Meditation” include a space where cushions are placed in a circular pattern, on a polished floor over which participants can see their own reflection. Pieces such as “Modern M” include a space where cushions are placed in a circular pattern. The circle is a highly glazed (auto lacquer) surface placed vertically (not the floor) in front of which is the meditation cushion. This in a sense balances another work entitled “Self Crucifixion.” Both works were done for Carlo Catellani’s collection.

“La Scala della Montagna” is a participatory piece in which sounds come from cowbells and resonant elements. Within the more corporal experience-related dimension, there are pieces such as “Several Sexuelementos” (“loving scores for private performance”) or his erotic writings obviously titled “Symphysies.” In some way, the period towards a conscious spontaneity involves a progressive integration of elements that will become more notorious during the current and last years of his career. This involves the moving body, the sound, the energies, the use of diverse materials (instruments, resonant metals, percussion elements, etc). To a great extent, ‘Gong/Ear’ or ‘Earth Breath’ concepts have a share of improvisation as a result of the interplay between musicians and/or dancers (or others: Corner’s knowledge about visual arts and his long-time friendship with Canadian tachiste Paul-Émile Borduas is worth bearing in mind). Each bodily or sonorous gesture or action can be commented on or discussed by the group on an open-duration basis. Exercises known as ‘Elementals’ explore the possibilities of primary structures: a single sound, silence, sustained tones, temporal extremes, the conversion of numbers into rhythms, among other options.

Spirit, Soul (Integration and Synthesis). Since 1999

An interesting title to unashamedly warn about some concepts which have been long banished from the avant garde and experimental art, as well as from a major part of the 20th century culture. Corner is not fearful of evoking concepts related to what seems to be the past of human history. In the same way, he pursues an interest (which he never lost) in the major musical works in history. A connoisseur of ancient music, the Baroque masters and the piano literature of the Romantic period, Philip Corner is able to mingle his own experimental radical nature with seemingly incongruent sources. This coherence of his becomes feasible by taking fragments of sheet music to be reinterpreted, such as in “Passacaglia” for piano (on Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber) or in “The Opening Motive of Varèse’s Density 21.5... as a revelation,” a kind of strategy that has enabled him to revisit Couperin, Chopin, Saint Säens and many others who sound rather hateful to the experimental environment. During January of 2011, the New York Times opened a survey to choose “the ten greatest composers of all time.” Quite annoyed at the understatement, Corner responded by sending a letter in which he explained his disagreement and the blunder committed by the prestigious newspaper. Exhibiting a tremendous knowledge and a remarkable capacity for problem-thinking, Corner started his discussion by pointing out twenty-seven critical items of technical innovation (within Western music, while acknowledging the fact that there is music elsewhere). The beginning: the shift from monophonic music (plainsong) to polyphony; point 27: the assimilation of extra-European techniques and instruments. While the average music lover would think of Mozart, Bach and Beethoven, Corner goes back to the Notre Dame School and reaches Harry Partch or Lou Harrison, thus expanding the initial list of “indispensable composers” from ten to ninety, among which the Salzburg genius is obviously included12.

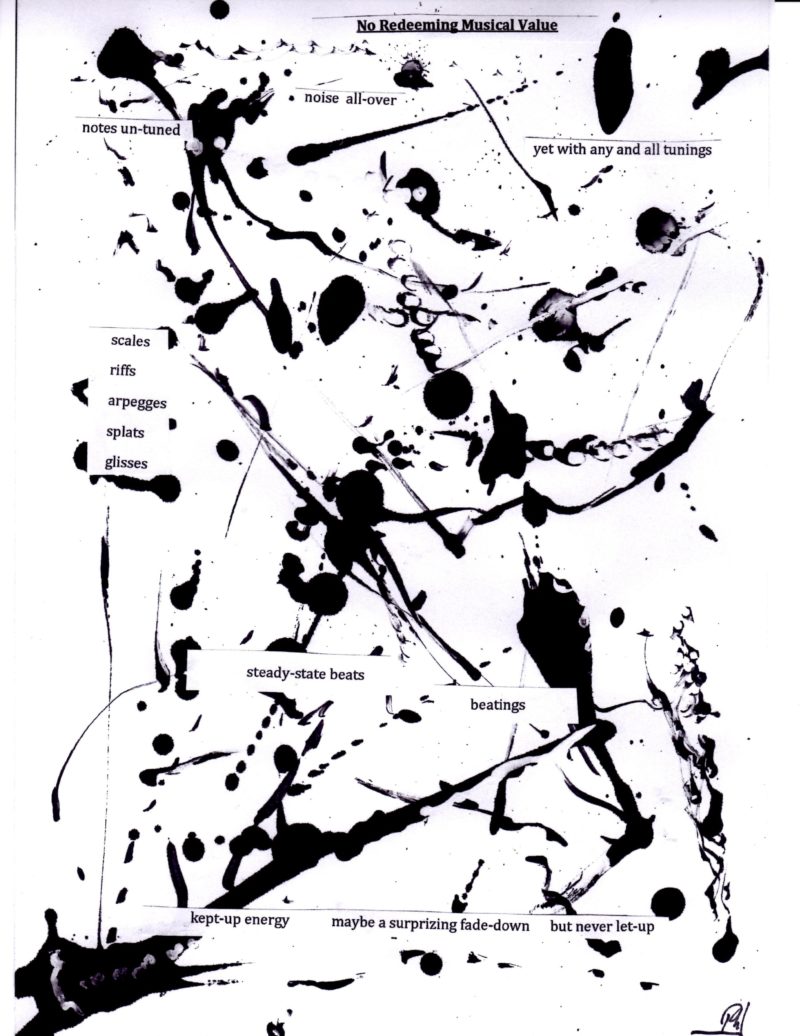

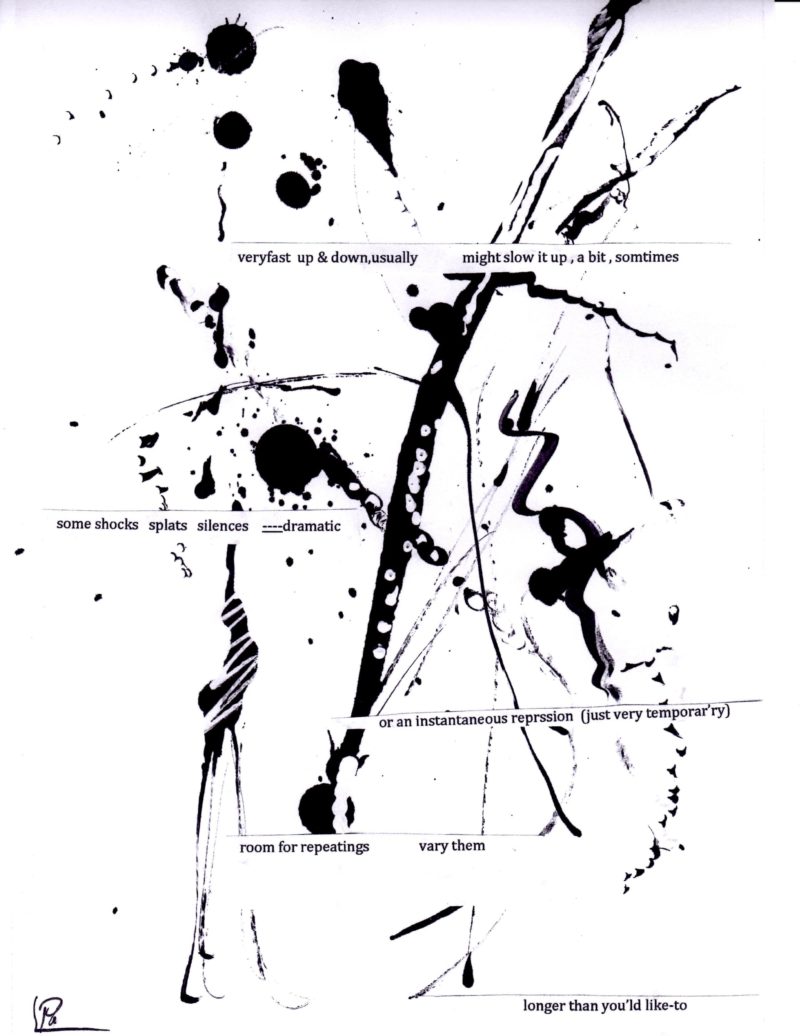

His instruction pieces seem to be increasingly open and poetic, leaving a certain degree of responsibility to the interpreter. In any case, several scores of Corner’s involve a great deal of playful spirit or sensuous expressiveness; however, he himself has often emphasized the dangers brought about by some interpreters doing “very disgusting” things with his work13. When concepts are respectfully recreated and expanded, with utmost generosity, Corner admits that “the merit must be attributed to the player rather than to the composer.” This integration can also be found in ‘Political Pieces’ (a series about social concerns) and in the title that provides the composer’s best example of that period: “Dialog between Rationality and Emotions,” suggestions for any number of instrumentalists.

Footnotes

- Corner, P: Lifework. A Unity. Frog Peak Music, Lebanon, NH, 1993. A descriptive summary of the author’s works and creative periods.

- Corner, P: In and About and Round- About in the 60s. Frog Peak Music, Lebanon, NH, 1995. It includes a detailed account of Corner’s stay in Paris, page 10 and following pages.

- Corner, P: Etincelles. In : Piano Works & Piano Plays. Volume I: Philosophical Etudes. Frog Peak Music, Lebanon, NH (without date of publication). Etincelles is a miniature similar to a high-speed arpeggio gesture which is repeated after a silence interval, with different dynamics in each note. It includes consonant and dissonant intervals, probably influenced by Messiaen, and dates back to the early 60s.

- Corner, P: NY 60s: Scenes from the Scene. Frog Peak Music, Lebanon, NH, 1995. It includes several references to Charlotte Moorman’s performances in the chapters about Judson Dance Theatre and the Fluxus movement.

- 5. There are three CDs including recordings edited by the Milan label Alga Marghen: On Tape from Judson Days C 4NMN.019 (1998), More From The Judson Years (Early 60s) Instrumental-Vocal Works Vol. 1 C 24NMN.055 (2004) and Vol. 2 – C 25NMN.056

- Corner, P: NY 60s: Scenes from the Scene. page 12.

- According to the Frog Peak Music catalogue, Corner’s Gamelan Series include “463 pieces currently available, all written as open scores (always some improvisation or indeterminacy, yet very formal), on, usually, graph paper. They can all, of course, be realized on the instruments of Javanese or Balinese gamelan ensembles --or American!-- or other groups of metalophones. They can also be transcribed for other instruments. In addition, those having already-been or can-easily-be realized by specific instruments, have been gathered into a set of booklets: a. Piano duets and multiples; b. Piano solo or other keyboard; c. Solos and duets; d. Events and objects; e. Percussion; f. Ensembles; g. Voices; h. Combos

- 8. Originally edited by the Folkways label in 1979, Gamelan in the New World is a Gamelan Son of Lion’s double album which features works by Corner, Daniel Goode, Barbara Benary and others. Long out of print, it has been reedited by the Locust record label in CD 41/42 in 2004.

- Corner, P: De Winter Course. Frog Peak Music, Lebanon, NH, 1994. An experience in the Ontwikkeling modern dance school in Amsterdam for a music program in which an exploration between sound and body was carried out.

- Corner recorded a series of improvisations using the alphorn and various metals throughout different periods in Cavriago, Reggio Emilia. His recording on June 16th, 1994 has been given over to the author.

- Gong (Cymbal)/Ear in the desert. Innova CD 227, 2009. An original 1991 recording made at a canyon located in the north of New Mexico.

- ‘Music History.’ Email from Philip Corner to the author, 11st of January, 2011.

- E-mail from Corner to the author, February 15th, 2011.

This article was published originally on perfectsoundforever.com. Big kudos to the magazine for letting us use their article.