Experimentation in the midfield: a night with Sote

Typical heartwarming restaurant jazz plays in the background as the sound of glasses and hands moving on the table blend with my voice suggesting Ata, Pouya, Arash and Rojin we do this interview in Farsi, our mother tongue.

Ata and I first met in Brussels almost two years ago when he headlined our first exhibition and party concept that later became what is now called KAVIR; a collective focusing on bringing together artists and musicians with both Eastern and Western legacies. I recall waiting for him at the entrance of the Galerie de la Reine. When I greeted him, a sense of endearment took hold of us, perhaps evoked by my Esfahani dialect. He gifted me an emerald colored box filled with Persian cotton candy which I later emotionally ate all by myself in the bathrooms of the Cinema Galeries just before the event was about to start.

Now sitting around a table in Ghent I meet Arash and Pouya for the first time as they join us to perform at Eastern Daze. Both are accompanying Ata Ebtekar to perform his album Parallel Persia released in April. Rojin Sharafi, a promising Vienna-based composer, who recently released her debut album on Ata’s label Zabte Sote, also joins. We have just finished dinner when Ata praisingly recalls the food my mother cooked for the crew and artists last time he was visiting Belgium.

I hear myself taking a deep breath through the recorder before I announce I am ready to ask my first question. “So first I would like to know…” but before I have the chance to finish my sentence Ata finishes it for me: “What perfume we are wearing?” Persian baba-humor (baba = father) fills the dining room and we all laugh. This form of humor, well-known for everyone sitting around the table, makes me feel comfortable. Ata jokingly tells me to stop being nervous. Despite having regained focus I can’t help but add up to his joke. “I was about to ask what brand of cigarettes you smoke, what sports you played as a kid and what your favorite food is. Let’s face it: all the music-related questions have already been asked and can easily be found on the internet.”

Niloufar Nematollahi

Arash and Pouya, I am interested to hear about your musical backgrounds and how you met each other.

Arash Bolouri

I wouldn’t say my dad is an artistic kind of guy, but his love for music is as sincere as his taste is broad. From Iranian pop to rock to traditional folk music, he had it all and wasn’t afraid to turn up the volume, especially on holidays! Pouya and I truly grew up together. We are like brothers. Our mothers became friends in primary school so we have known each other from the very beginning. We were always together. Our interest for music was also shaped in parallel.

Pouya Damadi

We always stimulated each other’s love for music.

AB

I mean, we always listened to music together and started playing our main instruments around the same time. My interest for Western music and love for Persian music developed at the same time. I always loved the santour. As a kid I remember wanting a miniature santour and trying to play it. When I was sixteen or seventeen I chose it as my main instrument for traditional Persian music training that I received from teachers such as Amir Rahmanian who was a student of the legendary Faramarz Payva. I worked strictly in his style at first. Although I learned a lot, after a while I realized I wouldn’t be able to find what I am looking for within this approach. I was listening to other genres and saw there were more interesting things happening that I wanted to discover. It drew me a modern style of santour playing with pioneers such as Ardavan Kamkaar and Siamak Aghaei. I went to Bahman Behmaram, a santour player who is known for combining Western classical music with the Persian tradition, not only regarding his way of playing but also his way of teaching. With him I felt as if I had started from the beginning again. He destroyed every structure and style I had worked with and we built it all up again together. I started composing with him and at a certain point he said his work was done and I should just start playing and experimenting on my own.

PD

As a child I mainly liked Maqam music. I first played tanbour and daf and at approximately the same time Arash started playing santour professionally, I chose tar as my main instrument. To be honest, I was and might still be the kind of fan of traditional Persian music who locks themselves up in their room and listens to the singing for hours. I just followed the same disciplined and conventional path everyone who is obsessed with traditional music and wants to play an instruments follows. I was fortunate to take classes with different tar masters over the years. I still love traditional music but by getting to know Ata’s work I realized there are other kinds of sound you could integrate in your sound. At the end of the day all acoustic instruments have their limits. The sound of a tar is what it is. The possibility to combine that with a sound of other quality and nature truly opened a door for me.

AB

I also came into contact with electronic music through Ata. The first time he came back to Iran after seventeen years I was doing some graphic design and he asked me to make something for him. It was then I learned more about his work. The design was never used but it did open a gate to paying attention. Now he was living in Tehran our connection became stronger as the physical distance had disappeared.

Ata Ebtekar

As Arash already said, his and Pouya’s mothers are best friends. The third side of this friendship triangle is my sister. Their friendships guaranteed us always being a spectator of each other's lives. I remember sitting down with Arash in his room during his teenage years listening to music together, talking about and showing each other music from our different backgrounds. As you know, growing up in Germany and later moving to California, my music roots lay in techno. One of the reasons I felt the need to go back to Iran during the time I was living abroad was because I wanted to introduce electronic experimental music and synthesis to the younger generation. You could say “introduce” but I actually just wanted to create a place where we could talk about it because I couldn’t find anything similar in Iran.

AB

By the second time Ata came back to Iran, I was taking music more serious and Ata was also determined to stay in Iran. That’s how we started talking about a collaboration.

Arash participated in Sote’s previous album Sacred Horror in Design and in the recently released Parallel Persia. He tells us how him and Ata came together a couple of times after Ata had moved back to Iran and talked about creating a project in which they would combine traditional and electronic music though it felt as if the time wasn’t right. First when CTM Festival commissioned Ata to create a live show, they collaborated on what would become their first album: Sacred Horror in Design.

Rojin Sharafi

Did you start of by improvising when you decided to work together on Sacred Horror in Design?

AE

As we said, Sacred Horror in Design wasn’t originally supposed to be an album but a performance. We focused on the live aspect of it and added the visuals. Towards the end we started seeing it as an album. Although the piece wasn’t solely improvisation and I had composed the electronic parts in advance, there are two improvised pieces on the album. One is fully improvised by Arash and the second one by Behrouz who played the setar. Of course I added layers to it later, but on those two mentioned pieces the base is their improvisation.

AB

The final result we perform is mainly constructed and produced by Ata but it also respects the original improv.

AE

For some tracks we leave a certain space to improvise during the live performances. People have written or said the album is all improv, which is not true. I’m glad the assumption is real enough to pass on the vibe of improvisation so that people think we improvise it all on stage. Structure is so important for me. Not only within the music I compose but also in what I listen to and that is the main reason I’m a fan of what Rojin creates. No matter how experimental or abstract it might sound, it remains a composition. For some people just the feeling of an amorphous atmosphere might be more important. For me, structure is the embodiment of the idea behind a sound. A composer might create these structures without even realizing it. It’s not always a conscious deed but it’s always clear in the final result.

NN

How did the collaboration on Sacred Horror in Design influence Parallel Persia?

AE

My biggest fear was that of repeating ourselves. The difficult thing was that both albums were very close to each other time-wise and the elements were also very similar: the electronic element, the santour and the tar. We replaced the setar we used for Sacred Horror in Design with tar for Parallel Persia, but by changing the instruments you don’t necessarily reinvent yourself. It can easily be a way of lying to yourself about reinvention and change. I love the first album and I wouldn’t change a thing about it, but Parallel Persia is stronger and more complete in terms of complexity and frequencies. It’s interesting to see that Sacred Horror in Design is seen as a dark album and Parallel Persia as a bright one. I think a lot of listeners were surprised because they couldn’t connect to Parallel Persia in the way they thought they would. Personally I think Parallel Persia is more virtuous in it’s approach as it has more dimensions. It has a very melodic dimension which makes it easy to connect. That same dimension may create a feeling of alienation as the possibly expected pop-like melody doesn’t take place.

NN

In Parallel Persia the traditional and the electronic elements that create the sound fully intertwine, while on Sacred Horror in Design they merely teeth off each other. At certain points they intervene and at other points they remain estranged from another. In Parallel Persia the estrangement remains but it’s nature changes. The two elements, apparently far apart, reach their climax together.

AE

Parallel Persia is a combination of everything I have done until now. All my previous albums coming together.

NN

In Parallel Persia the traditional and the electronic elements that create the sound fully intertwine, while on Sacred Horror in Design they merely teeth off each other. At certain points they intervene and at other points they remain estranged from another. In Parallel Persia the estrangement remains but it’s nature changes. The two elements, apparently far apart, reach their climax together.

AE

Parallel Persia is a combination of everything I have done until now. All my previous albums coming together.

NN

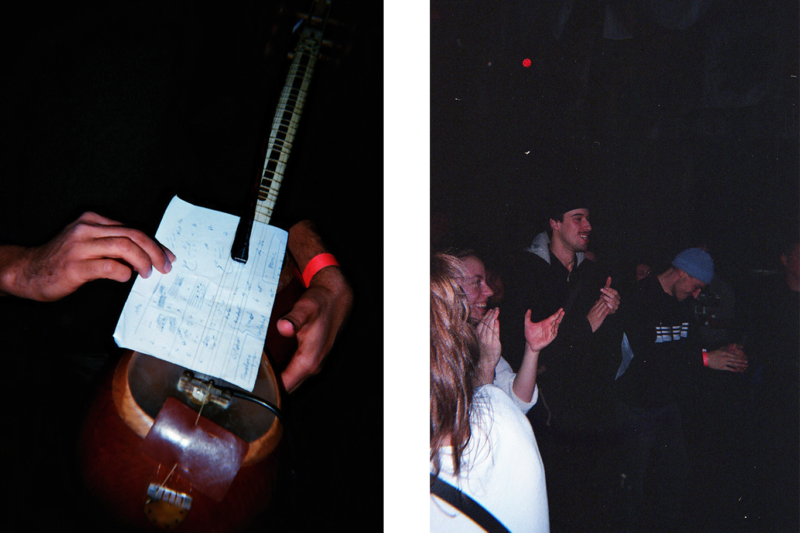

During the live show the santour I heard playing on our kitchen radio came together with a club-like bass. Two very different atmospheres somehow suddenly seem inseparable.

AE

What Pouya does with his tar is from an objective point of view so traditional – more traditional than how Arash approaches the santour. Pouya grew up learning how to play the tar in the most traditional way and loved it for what it was. The album is an homage that wants to filter the interesting aspects of traditional music by not paying any attention to the stigmas that make the genre considered as conservative. Those stigmas aren’t a trait of the genre itself. In the album, the sound that you just referred to as the sound you heard as a child on the kitchen radio goes together with the club-like bass. Like Berghain and Mohammad Reza Lotfi (Laughs). One of the most important elements to make these kind of collaborations possible is the trust that in this case Arash, Pouya and I have in each other. That is the most important thing when it comes to music and if it’s not there the outcome will show. Friendship and trust manifests itself into the will of sitting down with each other in a room for an unlimited amount of hours and bare each other and laugh with each other, listen and talk together and more important, get tired together. It has an effect on the music. I think that’s the reason why Pouya, although he comes from a very traditional musical background and even made fun of electronic experimental stuff stepped into this project and believed in it.

RS

We previously talked briefly about your love and preoccupation for form and structure. I can’t minimize the part of these two aspects in my own work as they go back to how I entered the field of sound making. Although I played classical piano from a young age and originally wanted to become a professional pianist, the reason I felt the urge to make music myself was listening to rock and metal. What played a role besides that was my love for cinema and literature. As a young teenager I learned to approach film and literature from a formal point of view and that’s also how I look at music. My interest in structure found its origin outside the medium of sound itself. My question is about where your appetite for structure comes from. Is a clear, chronological A-B-C matter? I’m curious about the way you personally think about form when it comes to composing. Is your way of thinking about form a completely abstract or almost mathematical? And does it find its origin in another medium?

AE

It’s completely intuitive. A lot of people think that all artists have a secret. I teach in Iran and when my students ask me about my secrets I’m always very honest about everything. I like to play open cards, especially when regarding the formalistic structures I tend to use. However I do believe that what feeds your mind, your personal style and feeling towards sound have an influence on what you create. Taste and technique can only grow with knowledge and experience. So when you know the “secrets”, by which I mean the A-B-C matters, but don’t have the intuition that feeds off of knowledge, it doesn’t work. Seeking knowledge and intuition always worked for me but that is of course very personal. Making something unique tickles me, straightens the hairs on my body. I can’t say that any other medium such as film or literature inspire me formalistically or structurally. Even if I would get inspired by something outside of the sound itself, I’d probably make one project with it and then go search something completely different and fall back to sounds themselves again. I have a certain kind of obsessive madness when it comes to change. As a teenager growing up in Germany I was madly obsessed with football.

Ata tells us that although we might not believe it, looking at him right now, as a kid he profoundly believed a life without football is not worth living. When says he used to play on state level in his small German town football team I ask him whether he’s a Perspolis or Esteghlal fan. “Back in the day I was an Esteghlal fan, but now when my son asks, I always say: the team that played the best.” Arash decides to remain silent and not choose one of the two teams because of the delicacy of the matter. “A man can have his secrets, you know; I want to avoid polarization.” We all laugh and, when the question is asked back at me, I clear my throat and announce, as a proud Esfahani, that I always have and always will be a fan of my desert city’s football team, Zob Ahan Esfahan.

AE

Believe it or not, even when I was playing football, being innovative was crucial to me. Being good at passing the ball was very important. Teamwork and playing our best possible game! I was busy studying the way the foot has to go by the ball, and how the grass would came lose from the field. I would pay attention and be obsessed by it all.

AB

You’re like that with anything that’s important to you. When I see you cooking you’re also like that.

AE

I’m not even exaggerating about how obsessed I was! On the weekends we would go outside in the fields to play. When I would slide tackle I payed attention to the way my leg would bleed based on which seasons it was and try to figure out how that could affect my game. Since football was the most important thing for me at the time, I wanted to pay attention to every single detail. When you’re obsessed with structure it comes back in everything you do because, at the end of the day, everything is like cooking or football. It’s not about the deed itself but the thought and structure behind it. I’d never thought about my love for football in that way. You really brought me somewhere I’d never thought I’d go back to. Especially not in the context of an interview. This now feels like therapy to me.

RS

I told her exactly the same when she was interviewing me.

AE

Experimenting is important to me but I loved playing midfield. A midfielder is just like a composer: you make the game. When we would go play in the fields in the weekends with my friends I would always get into arguments because, although I can’t play chess, I wanted to curate and create the game from the beginning until the end in all its aspects the way a chess player might. My friends would call me crazy and tell me to let go and just play. I did play and I liked it, but it was the making of the game I enjoyed the most.