Stephane Ginsburg

Brecht Ameel

Stephane can you tell us a little about your background, both as a pianist and as a listener?

Stephane Ginsburgh

My first experiences as a listener happened in a music loving family where I could hear all kinds of styles ranging from the early classical to the modern, opera, Lieder, chanson française as well as alternative rock, and even some electronic music. The transition to playing music was therefore quite natural and I started playing the piano when I was 6 years old. I never stopped since then. What followed consisted mainly in encountering musicians, all of them somehow influential in my evolution, and discovering the vast territories of music and knowledge in general.

BA

Do you remember when you became aware of Dennis Johnson’ s music? What was it that attracted you to his work in particular?

SG

I have been familiar with so-called minimalist music for many years when I participated in my first recording of Morton Feldman’s music for Sub Rosa with Le Bureau des Pianistes in 1990. Minimalism has played an important role in the way I consider doing music today.

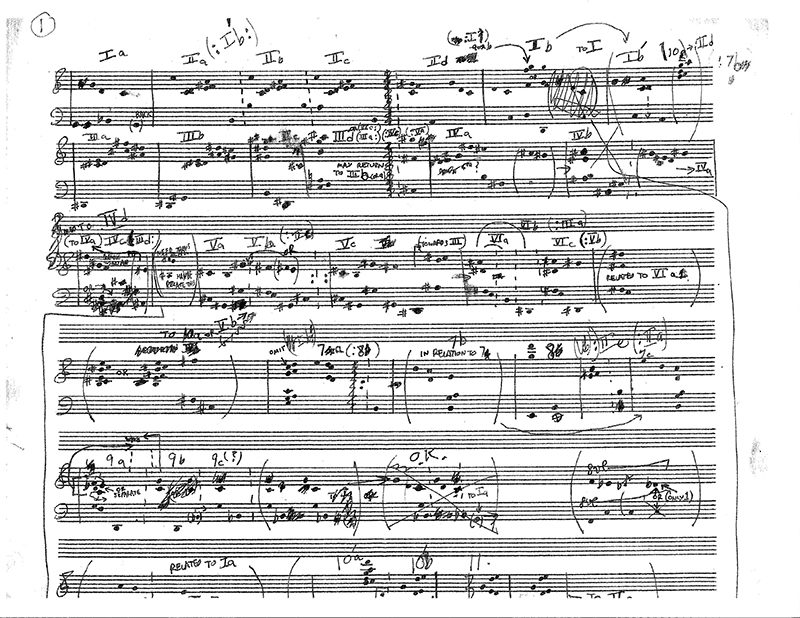

In 1992, American composer Kyle Gann received a tape and a few sketches of Dennis Johnson’s November from La Monte Young. Young told Gann that the piece had influenced him a lot in writing his Well Tuned Piano. And it’s only quite recently that Gann proceeded to work - hard - on the material he had received in order to reconstruct what seemed to be a 5 to 6 hours long minimalist and tonal piece, probably the first one of its kind. I became aware of the piece when pianist Andrew Lee released his recording of it a few years ago.

BA

Do you think there is a reason why Mr Johnson chose ‘ November’ rather than ‘December’ or ‘January’ ?

SG

I haven’t found any information about that except that one fragment is dated from early December which could mean that the piece was started in November. But that’s only a very weak hypothesis.

BA

Is the indication to start off with a ‘Very Slow’ tempo Johnson’s, or is it an addition made after Johnson’s own recording was discovered?

SG

The indication is not found on what seems to be the original sketch and might have been added by Kyle Gann after listening to the recording.

BA

If there would not have been any indication, how would you decide on a tempo for a piece like this?

SG

Well, in this case, the recording is important in reconstructing the piece and apparently, the tempo IS very slow. On the other hand, the style is clearly minimalistic and invites the performer to play slowly. This is also the case with some of Feldman’s pieces which have no indication but cleary belong to a universe of slowness.

BA

I mean this in the sense that with instrumental pieces which obtain a sort of ‘canonical’ status, there often tends to be a sort of established notion about tempo. For example, a Satie Gnossienne needs to be slow. No one dares to take it fast (anymore).

SG

Of course, but there still remains quite a large range of speeds even in slowness. You can always play slower than slow. I think speed is not necessarily an absolute data but also depends greatly on the length, the harmonics and the quality of sound.

BA

If you could choose, who would you like to be: the performer of “November Music” or a member of the audience who hears the performance?

SG

I always prefer being the performer but I think in the end that in all musical experiences, the performer and the listener tend to merge somehow. We are not considering anymore performing as the active part and listening as the passive one. Every person present become an actor in the listening experience. The performer simply being an operator of sound or a transmitter.

BA

I wonder how much of any current recording of “November Music”, or any current performance of this piece, is actually an improvisation based on just a couple of ideas that were outlined by Johnson?

SG

Well, the piece is basically a series of harmonic patterns which are played rather freely. There is absolutely no notated rhythm. So you could say there is some improvisation involved. But improvising does not mean you do whatever without reason. The material somehow always imposes its own way to the performer. As Feldman once said to Stockhausen: “You don’t push the sounds.” This means for me that the sounds themselves take part in the way they are played.

BA

Do you need to physically prepare yourself for this piece? Or is it a mental thing?

SG

I do indeed prepare myself physically because playing for 5 hours is quite demanding for the back. The longest piece I have ever played was Feldman’s For Philip Guston which lasts 4 1/2 hours. But I know pianists who play much longer. The mental preparation is very important in order to remain concentrated for a very long time. One of the best exercises I know for this is walking and mountain hiking.

When I listen to piano music of Dennis Johnson, La Monte Young and Morton Feldman (to name three composers who were involved in creating looooong piano pieces) , Johnson’ s seems to be the most clearly overtly emotional. Would you agree on this?

SG

No I don’t agree. I think music rouses emotions, but it does not contain any. Music is made of sounds and as such, it can touch the listener in many different ways. The difference between Johnson & Young on one side, Feldman & Cage on the other, resides in the fact that the first ones rely on tonality while the two others are mostly atonal.

BA

Music of long duration… I can’ t wrap my mind to decide what is the most thrilling moment of a 5 hour voyage: the beginning, when all is still open, and you wonder what will be next, where and how it will grow, what it will lead to… or the end of such a piece, when all of the notes themes reverberations suddenly turn out to be a conclusive thing, leaving a listener with a ring in the ears to take home and brood over.

SG

I sometimes wonder if there is a beginning and an ending. There are certainly in the performance, but not in the music. Music is almost infinite.