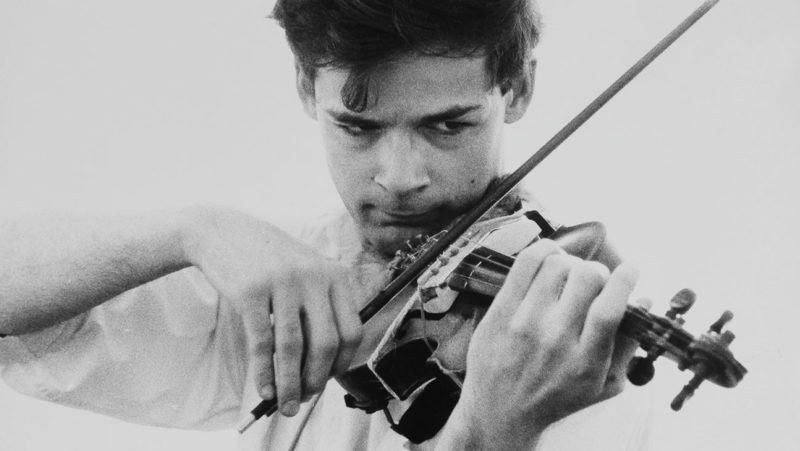

Tony Conrad

The Ghost Of Tony Conrad

It’s funny to realize that Tony Conrad was in my life much sooner than I ever could suspect. He played somewhat of a role in the founding of The Velvet Underground, he never joined them, though he was member of the proto-VU band The Primitives. His influence can so clearly be heard on Venus in Furs and Heroin, both tracks from their debut The Velvet Underground & Nico. The first time I heard Tony Conrad’s music I almost immediately caught myself thinking: “Hey, this sounds like the viola playing on Venus in Furs.” Tony had already been there, without me knowing.

Minimalism too wasn’t new to me. I had read about and listened to Glass and Reich, I’d read about LaMonte Young but I never encountered any mentioning of Tony Conrad (or Henry Flynt for that matter).

Later on I got more acquainted with Tony’s work through Dry Bones in the Valley (I Saw the Light Come Shining ’Round and ’Round) being the last song on Upgrade & Afterlife by Gastr Del Sol featuring him on violin, his own album Slapping Pythagoras (1995) on the ceased record label Table of Elements and Happy Days (1997) by Jim O’Rourke, an album that is seriously indebted to Tony Conrad’s work, this is well possible since both Jim O’Rourke and David Grubbs assisted in the making of his comeback album Slapping Pythagoras which was engineered by Steve Albini and enabled by Table of Elements owner Jeff Hunt.

It’s no coincidence that Conrad appeared at first in my life as a ghost, haunting the legacy of the great names in recent music history. It says a lot about his deliberate positioning in history, and towards his peers. It is the result of a consequent applying of his theories about history, life, reality and art.

“You don’t know who I am,” says Conrad, “but somehow, indirectly, you’ve been affected by things I did. I don’t mind being anonymous though. I hate celebrity.” (source: Ben Beaumont-Thomas article, The Guardian)

Conrad?

Tony Conrad was an artist of many disciplines. He was a violinist, a filmmaker, a painter, a sculptor, a media artist, a performer. You could say he was a mixed media artist, although he hardly ever mixed the different media he used. You could say he was multidisciplinary, but he just used whatever discipline he could use to express his vision which lied at the core. He didn’t aim at excelling in any discipline. He didn’t want to professionalize.

The documentary Completely in the Present by Tyler Hubby gives an interesting overview of Tony’s career and life. You get to see both artist and person and how interwoven they were. The movie discloses just how simple and direct Tony’s art is and how simple and down to earth art can be. It shows also how much of Tony’s art indeed is about being completely in the present, about the instant effects and workings of what he was doing, just as much as it was (and is) a comment on art and society in general.

His style of playing the violin was about “listening what’s in there, what is in the sound.” Listening to his music is pretty much the same, it’s about listening, about paying attention to the sound itself and to hearing what is going on within that sound. Listening attentively to any sound puts you in the present, be it the city soundscape, a dawn chorus, the roaring of a steel mill or Four Violins (1964). It’s a way of meditating, a way of connecting to here and now. His music is like that and his abstract films are like that, they put you in an undeniable and non negotiable present to which you have to respond. As often, surrender is the path to revelation, and that’s when shit starts to happen. If you give it a chance.

His music and his work is not about sentiments. There’s no narrative. There’s no climax. There’s nothing but sound. There’s nothing romantic about it. It’s about listening. It’s not about cosmic harmony. It’s non-Pythagorean. It’s political. It’s psychotropic.

His work is not about beauty. He is not even questioning beauty. Beauty is not the subject. It’s about what is there, about being curious and exploratory. “When I have this feeling that I’m working in some territory I can’t clearly identify, I feel enormously encouraged. Because it means I’ve found my way to something important that’s not been recognised.” (source: Ben Beaumont-Thomas article, The Guardian)

In fact, he wanted a lot of things to come to an end, to die. In the film, he can be heard saying: “I wanted to end composition. I wanted it to die out.” On the Wiki page about Tony Conrad he is quoted on his pickled films: “I was trying to kill film. I wanted to let it lay over and die.” In the booklet of his album Slapping Pythagoras he states: “Demolish the hegemony of monopolistic culture industries!” “It appeared as if Schoenberg had destroyed music,” he says, of the Austrian composer who had ripped up the rulebook. “Then it appeared as if Cage had destroyed Schoenberg. Our project was to destroy Cage.”(source: Ben Beaumont-Thomas article, The Guardian)

Meeting Conrad

I had the pleasure of seeing Tony Conrad perform live at least two times, one time in Brussels in 2000 and one time in Hasselt in 2005 at the Kraak festival. I had the even greater honour performing with the man when I was invited by Xavier Garcia Bardon to join an ensemble of guest musicians to perform Forty Five Years Alive on the Infinite Plain at BOZAR in 2007.

The BOZAR performance was a transformative experience, just like hearing his music for the first time, and it taught me a great deal about his work and his thinking:

- Meeting Tony Conrad in person and feeling his energy and his down-to-earth attitude was exhilarating and eye opening: this was not a pretentious and difficult art fart, not thinking highly of himself as one of the key figures in history.

- Getting instructions: “The piece is political, there will be two groups of performers, one on each side of the room, one side is the progressive side and is allowed to perform more free while the other side is the conservative side and has to perform as rigid as possible.” I got the very simple instruction to play the D note on my bass guitar as consistent and as regular as possible in a slow tempo. The bass guitar at the other side was allowed to be more free and was performed by Stefaan Quix. I remember Stefaan freaking out at the other side while I was being as monotonous as possible. It was a strange, intense and transformative experience to play D for an hour and a half.

- Getting complimented afterwards by Tony Conrad: “You, Sir, did an amazing job!” I’m still a bit puzzled by this or maybe overwhelmed by his generosity. After all, I only played D for an hour and a half.

- The lingering resonance within me this performance has had and the insight into the structure of the work and into his way of thinking only made me even more appreciative of the man and his work.

Completely in the Present

To be completely in the present is to be at terms with what is presented to you in the time and space that you are. To be open and accepting to what is in the now.

It could be a paradigm out of a new age book. That’s interesting. New age is often about harmony, peace and acceptance; up until the moment something less appreciable needs to be accepted. New age philosophy is very Platonic and Pythagorean in its fundament, it is very often about the harmony of everything. It feels paradoxical in relation to his work, as Tony Conrad is anti Pythagorean and hardly new agey. Yet, to be completely in the present, is to be fully aware of that moment without looking backward or forward, without taking frameworks or external authorities into account. The only authority is the here and the now.

To be completely in the present, to be completely focused on and absorbed by what you are doing, and in extension to mere being, is what Zen (and Buddhism) is all about. Much of the contemporary art music that comes from the United States since the 1950’s of the last century is conceptually indebted to Zen and Buddhism, to being in the present and in the now. Much of this music is very much about listening, about paying attention to what’s happening, of being aware and mindful. Also a great part of American avant-garde music and of what happened in the Fluxus movement is largely inspired by Zen philosophy. The awareness of silence and sound, the space between notes, listening thresholds, long duration, aleatoric composition strategies, indeterminacy, improvisation, conceptualism even, all of these ideas can be led back to Eastern philosophy and Zen more specifically. Hardly so in the European tradition, which up to this day, is still very much struggling with the romantic ideal of the suffering genius composer, the brilliant mind from which stems the most amazing art since the creation of the Universe (notice the sarcastic harmonics). The European tradition was still very much about being in control, about virtuosity, about predeterminism, about anthropocentrism even, whereas the American tradition went against that. There’s an interesting irony, in spite of a better word, in the fact that certain movements in the European avant-garde of the early twentieth century did however inspire the American avant-garde of the fifties and sixties. There is a lot of futurist and dadaist ideas that have inspired the fluxus and post-fluxus art. Could it be that good old Europe got too tangled up in post-romantic wars, unsuccessfully struggling to shake of the old and hopelessly looking for the good? Could it be that the reckless spirit, the headiness, of the New World was what was necessary to fuse these revolutionary early 20th century European ideas with ancient revolutionary Eastern ideas into a more successful strategy for breaking with the Romantic nightmare?

Tony Conrad’s music, and as a matter of fact much music out of the drone category, puts you completely in the present or put differently, it can place you outside of time. There is hardly any linearity in the composing, there is no melody, there is very slow development if any, no looking back, no looking forward, there is only the attention for what is presenting itself to the performer/composer/listener. It’s hardcore mindfulness, really.

But, being completely in the present is not only about the formal aspects of music, it has a great political and philosophical backbone to it.

Authority

One of the enigmas that I encountered early, was the fact that Conrad isn’t part of the parthenon of great composers, although he was part of the scene. This is addressed and clarified in the Tyler Hubby film Completely in the Present. Like Flynt, Conrad was a visionary and way ahead of the league, but that only comes clear in a debatable retrospect. This debate is also described in David Grubbs’ wonderful book Records ruin the landscape — “a book that owes as much to conversations with Tony as to any other resource”, says Grubbs in his appreciative article.

Grubbs’ book is about how recordings played a role in the sixties avant-garde, in the book he mainly focuses on the work of John Cage, since Cage is also known for his aversion to records. However, the first chapter of the book tells the story of Henry Flynt, occasional partner in picketing with Tony Conrad. Flynt, having made recordings throughout the sixties that only surfaced towards the end of the nineties of the twentieth century. Flynt is known to have considered it necessary to go back into the art world after a hiatus of about twenty five years, to update his views. It does pose the question of how much (unreleased) recorded archives are still there and how recordings can be used in some sort of retroactive way for justifying someone’s historical relevance, even though never having been released at the time. These records are records of ideas, of new ways of thinking. These records can also be used to testify for or against someone’s importance and ego.

This is also what lies at the heart of the lingering conflict between LaMonte Young (LaMonty Burns) and Tony Conrad over the archive of recordings made by the Theatre of Eternal Music. Theatre of Eternal Music was a collective initiated by LaMonte Young in which Tony Conrad played a crucial role by introducing the violin and the use of just intonation. The whole goal of the collective was to annihilate the idea of a composer and to just play this sound, this music, that was never played before. It was a collective effort of LaMonte Young, Marian Zazeela, Angus MacLise, John Cale and Tony Conrad, amongst others. It is therefore quite contradictory to learn that a) Young does not want to disclose any of the recordings, not even for private listening, b) Young claims to be the composer of all this material.

What use is a recording of an idea when it is not released? Doesn’t the idea get picked up by whoever attended the recorded event and thus resonates further in that manner? Doesn’t the initial recording, upon release somewhat thirty years later, try to lead back the idea to its source?

What is a composer? What is authorship? What is authority? What is LaMonte Young trying to achieve by holding onto those two years of recordings of Theatre of Eternal Music? According to Conrad it is “because they don’t show him [Young] in as strong a light as he would wish” and he continues to say that Young’s music is “unashamedly founded in individualistic romanticism”. (source: Hyperreal.org) That is also probably why Young tried to force both Conrad and Cale to sign an agreement that he was the single composer of the music of ToEM, which was clearly a collective effort, but not so in the eyes of Young.

The Origins Of Western Culture

Tony Conrad is about egalitarianism and freedom. He’s obviously asked the question so many of us struggle with: “What’s happened to our culture? Why is the system so sick? Why aren’t we free?” or any other question that relates to inequality, hierarchies, fake democracies…

Conrad is very much referring to Ancient Greece and how Western civilization is still firmly rooted in that old European thinking tradition. In his unfinished film Jail he presents a prison for women, but all the women are played by men, like in a Greek tragedy where all the characters were always performed by men, even the women. However, the men dressed up as women are placed in a jail. Could this be a metaphor

The typical way in which he presented himself during live shows, always projecting his own shadow, is an almost literal reference to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and the more elaborate theory of forms (or theory of ideas). However, Tony Conrad shows both the shadow and its origin. He shows the projection of the idea and the ideal and discloses the both. In doing that he breaks with the ancient idea of Plato that says there is a world of things (shadows) that is imperfect and earthly and a world of ideas that is perfect but unreachable. Pythagoras installed the notion of the harmony of the spheres and the suggestions that there’s a higher order of things, an all encompassing harmony, a divine regulation, a cosmic set of rules according to which everything needs to be governed. “BULLSHIT!” exclaims Conrad. He wants to break this dualism, this division between the heavens and the earth, everything is here and now, completely in the present. Once again, the influence of Buddhism and Zen on post WWII America’s art becomes clear. Not so in good old Europe where it is still believed change lies in the alteration of the tradition, always looking back, always stuck in ancestry. His criticism on both Stockhausen and Schoenberg is similar to that on Young, all of them composers according to the romantic idea of the individualist genius.

He explains his theories quite clearly in the booklet of Slapping Pythagoras in his typical humoristic and punk style, partly addressing Pythagoras directly and partly teaching his own theories. He alleges Pythagoras of taking his ideas from Egyptian and Babylonian culture in the first place. Then he also blames Pythagoras for elitism and for undermining true democracy. His arguments are lucid and solid. This is not just reactionary behaviour, this is well thought over. Pythagoras’ theories and teachings lead away from the present, from the here and the now. Pythagoras’ believed in a world that could be improved, in a Universal order that served as a model for the organizing of society. Clearly this is not Tony Conrad’s conception. “Pythy” is responsible for the non-inclusive character of modern day Western society and for today’s inequality. The Universe of Pythagoras is exclusive and homophonous, that of Conrad could be inclusive and heterophonous.

His music is a display of heterophony, as opposed to homophony. Hetero means different, homo means same. Compare it to heterogenous and homogenous. Tony Conrad’s music displays heterophony in that it does not strive for harmony according to Pythagorean arithmetics that are depending on discrimination of certain musical intervals to achieve harmony. Conrad’s music goes against this by introducing and allowing all intervals that go against the “harmony of the spheres”, against the mathematical order that was discovered and introduced by Pythagoras. He is interested in what happens when tones and frequencies clash, when different mathematical intervals are introduced into his drones thereby producing a sound that reconfigures your brain and everything you know and have accepted as Western culture. “If you give it a chance.” — says Larry Seven about The Flicker, an experimental film that investigates into mathematical patterns in similar ways. This applies to much of Tony’s work, it transforms your way of listening, if you give it a chance.

He’s pondered these questions and has gone back real far to the origins of Western Culture and Western thinking, to a culture that foregoes even Roman culture — let’s say that those Romans just helped spread the disease/ideas (there’s ideas in disease), to the roots of European thinking in Ancient Greece. The Old Greeks are generally considered to be the inventors of the celebrated idea of democracy, a system that, just like communism and as far as I can see capitalism, never has been executed properly. For some reason those great political, economical and social theories have been corrupted as soon as they were made up. Democracy was corrupted by Pythagorean elitism. Communism by Totalitarianism and Capitalism by an inversion of its own principles.

He was a genius, from the gut, from the underbelly. It’s as simple as that.