Gobelijn, Vanhoof, Lagaffe

The Internet says that Pablo Picasso may have once famously mentioned that 'every child is an artist'. Although there seems to be little hard evidence for the quote, many artists and intellectuals before and after him have investigated inborn imagination, and how that same imagination is ruined by some evil spirit called politics, pettiness or other synonyms for society. For example, in an interview Antony Fawcett conducted with John Lennon and Yoko Ono at Apple Records in 1969, Lennon stated that 'every child is an artist until he's told he's not an artist'. The reverse idea, that every artist is a child, is less common in art criticism, even though there is a simple logic behind it. If every child is an artist, the artist should at least have some kind of urge to return to that natural state of artistic being.

In popular culture, the ultimate embodiment of imagination or artistry is The Inventor, the professor who, through his ability to combine childlike imagination and a developed sense of reasoning, makes the world a better place. It is not necessarily the product of that ability which is appreciated by the public, but the appetite for engaging in this process. The Inventor is popular both among children and adults, and therefore often featured in comics, the ultimate medium in which children and adults find common ground. Two renowned Belgian examples are Gaston Lagaffe and Jeremias Gobelijn, the brainchildren of André Franquin and Jef Nys, respectively. Both characters always achieve excellence, be it through failing, or by failing as such. Yet, this is only important for the narratives. The likeability of the characters is in their spontaneity with which they, each and every time, plunge into the realisation of their ideas.

Appreciation for Floris Vanhoof and his oeuvre follows a similar track. There is a jolliness in his devotion, which gives the artist and his work the authentic aura of Imagination, and ultimately leads to a strong connection to the elementary representation of The Inventor. Moreover, his body of work relies heavily on invention (as in ingenuity), be it producing electronic music and flicker film as direct products of alpha brain waves, or using the tusk of a beetle to replace the needle of a record player.

The professor and the infant perfectly merge as a single persona in Jommeke nr 90, 'De kleine professor' (The Little Professor). In an attempt to solve the problem of overpopulation, Gobelijn has invented a potion which will make everyone smaller. When he mistakenly drinks a glass of the potion instead of his freshly made berry juice, his body turns into that of a small child, yet keeping his giant walrus mustache. This means that his childlike imagination now also coincides (at least partly) with its bodily representation. Gobelijn has become an actual manchild, apart from a casual outburst of whining, only sporting the positive traits that come with the transformation.

It is not hard to interpret the transformation as a metaphor for the constant flux in the artist's grandeur. Imagination only works through the method of changing perspectives, i.e. blow-ups, close-ups, distance. (cf. other famous examples such as Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Honey I shrunk the kids, The BFG, Gulliver's travels ...). The same applies for the ego of the Inventor, which can at times be shy and modest (even insecure), then proud, swollen or pompous.

I have always valued Floris Vanhoof's dialectic of modest art practice and magnanimous realisation, as a little professor in a quest against pettiness, destined to find an antidote.

I remember the first time I set foot in Vanhoof's old house in Meulesetede in Ghent - maybe not coincidentally only a stone’s throw away from Phill Niblock's Experimental Intermedia residence -. His living room was a small museum stuffed with colourful comic book nostalgia, oddball collectables, sci-fi paraphernalia, psychedelic furniture and half open parcels with synthesizer elements. Vanhoof showed me a recent acquisition of some long-forgotten fanzine for Dutch speaking synth freaks in the eighties. His fascination for that scene eventually led him to compile a tribute double cassette of amateur electronic new age musicians who sent their recordings to the now legendary BRT2 radio programme 'Maneuvers in het Donker' - presented by a priest called Flor Berkenbos. Anyway, I felt like I was in an experimental play castle, built by Charlemagne Palestine, in which the kind wizardly host was about to cook me in a giant pot of esoteric electronic stew. I later also helped moving a freaking heavy ancient synth to another floor in exchange for a wrongly ordered Technics record needle. The opposition of the grotesque and the miniature appears to be a recurring motif in Vanhoof's life and work.

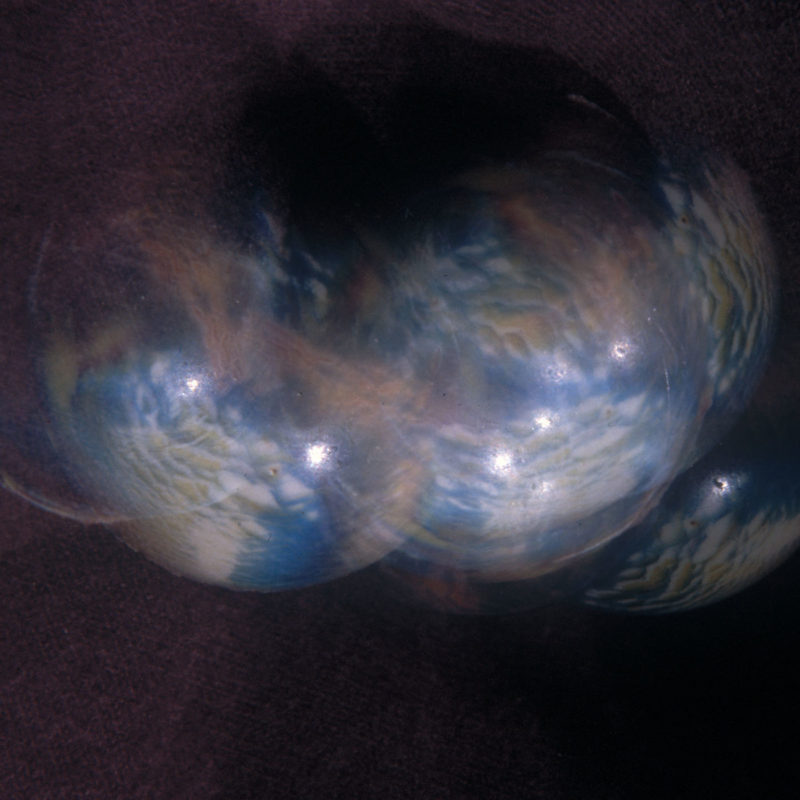

The method lies in alternately zooming in and out. One example of this in Vanhoof's body of work is 'Fossil Locomotion' (2016), which focuses on the fossils his family has been collecting over the past decades. Blow-ups of different fossils merge within a single second in a slide carousel. The subject matter is both close to home and spanning Deep Time, stemming from amateur paleontology, but conveying a message far beyond it by animating something that is inherently immobile, then again compressing it into micro time slots. The core question that sparks the piece is a childlike one: 'What if these fossils could move again?'. A similar combination of time contemplation and microscopy is 'Bug Sounds / Vinyl Canyon' (2016). In this installation Vanhoof seeks primitive forms of sound waves, both in sound and image. The needle of a record player is replaced by a beetle that uses its tusk to to translate the circling grooves of a specially designed record to sound. The sound is an electronic composition of Vanhoof for the slide projection that is played simultaneously. The slides show microscopic images of the grooves. The spectator thus shares the perspective of the beetle. It is an invention in its own right, a means to comprehend the perspective of the insect while detaching it from its habitat, and at the same time giving it a new function. The dead insect is celebrated in the work, both in the aesthetics of its form and in its new abilities that transcend anything it could have possibly meant whilst being alive. There is an eeriness to it, but in a zany way. I remember seeing the installation in an old warehouse in Brussels, during an artist collective-run festival. Some random bands were playing in the basement, being their most tedious or most deafening selves. Me and my friend kept returning to the enchanting work, basically spending our evening in the presence of the bug and its message. Vanhoof was providing context to interested passers-by in the half-dark. His girlfriend was being very charming, discussing her lover's social qualities and the children's books of his uncle Guido Van Genechten, some of which my young son really adores.

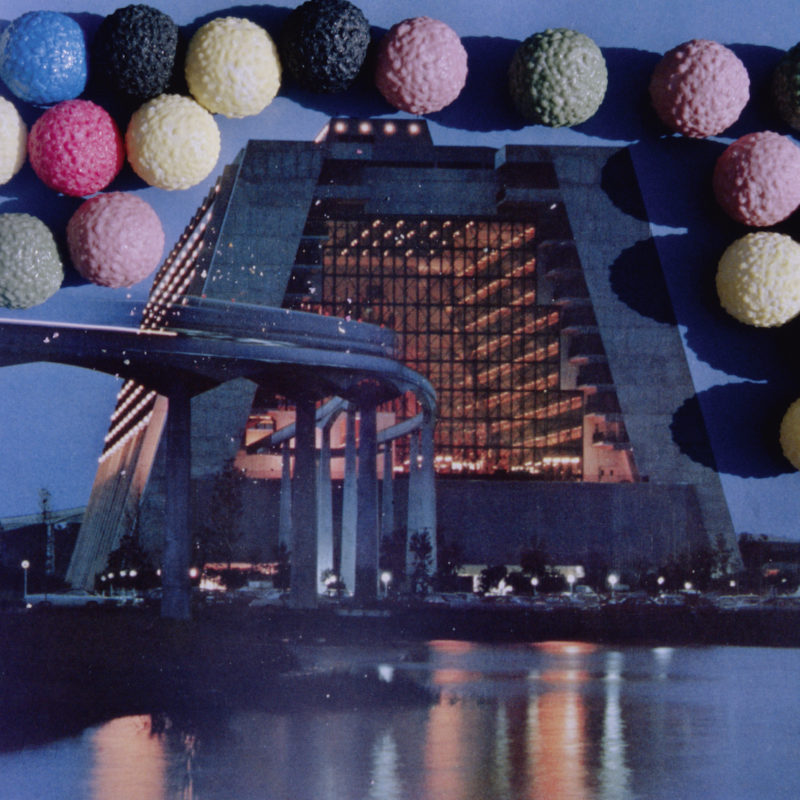

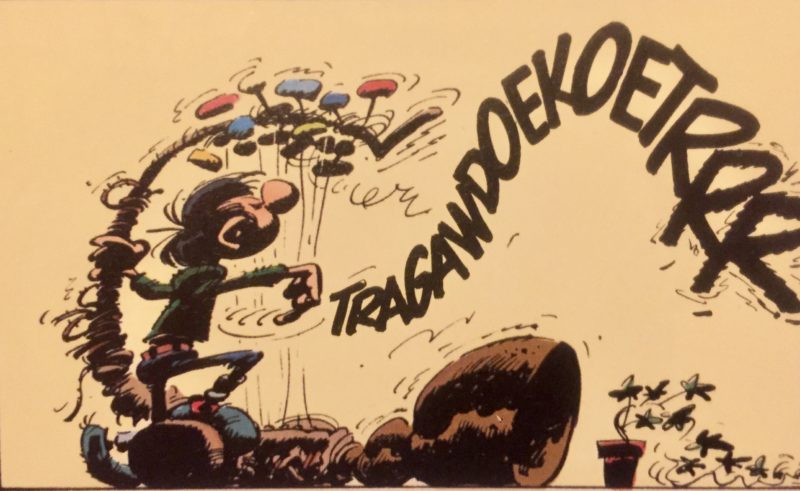

Jeremias Gobelijn and Gaston Lagaffe differ from each other not only in physical appearance - Gobelijn being the stereotypical elderly know-it-all: short, balding, overweight, always in costume, and Gaston: tall, gawky, in worn out jeans and a woolly sweater - their general demeanour shows two ends of the continuum of representation of The Inventor. Gobelijn is close to the archetype of the 'mad professor'; he is absent-minded, always mixes up idioms, and always has to solve his own mess-ups. He is the 'mad-but-funny' type of character ('mad' as in a mislabeled form of 'confusion'), soft around the edges. Gaston, however, is more of a rebel kind. He's more of a hippyish punk anti-hero who sits around all day at his job, annoying his colleagues with new chemical inventions (most of which explode as a climax). His inventions are much closer to a contemporary art practice than Gobelijn's. He is also a music lover, often sitting around playing the guitar or the tuba, or even famously inventing his own instrument, the 'Gaffophone' (or 'Brontosaurophone' as Gaston calls it), a monstrous instrument which is partly a hollow tree stump, partly giant harp. It is known for destroying entire neighborhoods once it starts resonating. Vanhoof has a lot in common with Gaston. There is a strong physical resemblance: Vanhoof as well, is tall, slender and I have seen him more than once sporting old shapeless jumpers or a washed out Nirvana shirt (come to think of it, his girlfriend is not entirely unlike Moi'selle Jeanne either). 'Klanken om in te wonen', an audiovisual promenade that was presented in KC Belgie in Hasselt in 2013, featured a musique concrète installation that could easily be labeled as Vanhoof's rendition of the Gaffophone. Against the back wall of a room is a grand piano on its side; next to the piano, a wooden framework filled with internal elements of another grand piano. Above the pianos, gongs of different sizes, bells, a kettle and multi-coloured crochet blanket are hanging in the air. Somewhere there is also a plastic crab and a vintage rubber frisbee. Contact mics and guitar pickups are attached to different parts of the installation. The visitor has to take a tennis racket and smash the balls into the installation to contribute to the post-Cagean chance operation composition. In terms of cheerfulness not much has changed since I first saw Vanhoof hanging upside down on a trapeze, bare-chested, blowing a trumpet while lighting fireworks from its bell. That was during one of the legendary shows of Dirk Freenoise (somewhere in the mid 2000s) a neo-dadaist noise band that could easily have been part of LAFMS-scene if it weren't for the fact they were teenagers based in Brussels and Antwerp.

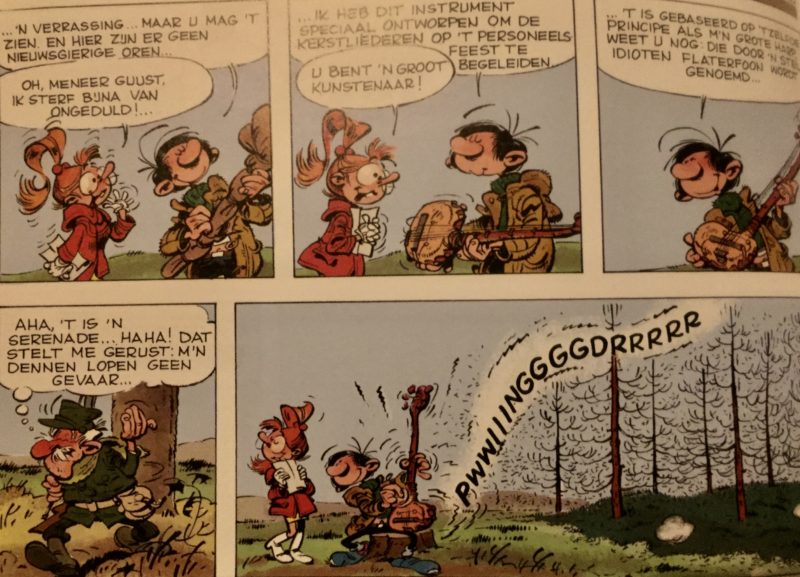

A constant craving for new sounds is another constant in Vanhoof's oeuvre. Parts of 'Time Slime' (Ultra Eczema, 2011) consists of throwing parts of a drum kit down the stairs of an empty church, 'Cycles of Confusion' (Kraak, 2012) include field recordings of a pinball game, a classical orchestra tuning their instruments and a chance encounter with a New Hampshire brass ensemble. Not to mention many micro releases documenting his research to ever new ways of approaching the modular synthesizer. Unlike some of his visual work, sound here speaks for itself. The invention is a transposition of the idea to sound as such. 'Pourquoi philosopher alors qu'on peut chanter', a quote by Georges Brassens introduces a gag in which Gaston drives Jeanne to the forest where he wants to impress her with a brand new invention: a small lute-like version of the Gaffophone. It works, Jeanne exclaims that Gaston is a great artist, and when he starts playing she blushes in awe. The pine trees nevertheless can't handle it and immediately start losing their needles. His music unintentionally only satisfies the few aficionados. Noise is often celebrated in Gaston (climaxing in Gaston's own band King of Sounds, which literally break down the house - they look like a primitive version of Dirk Freenoise).

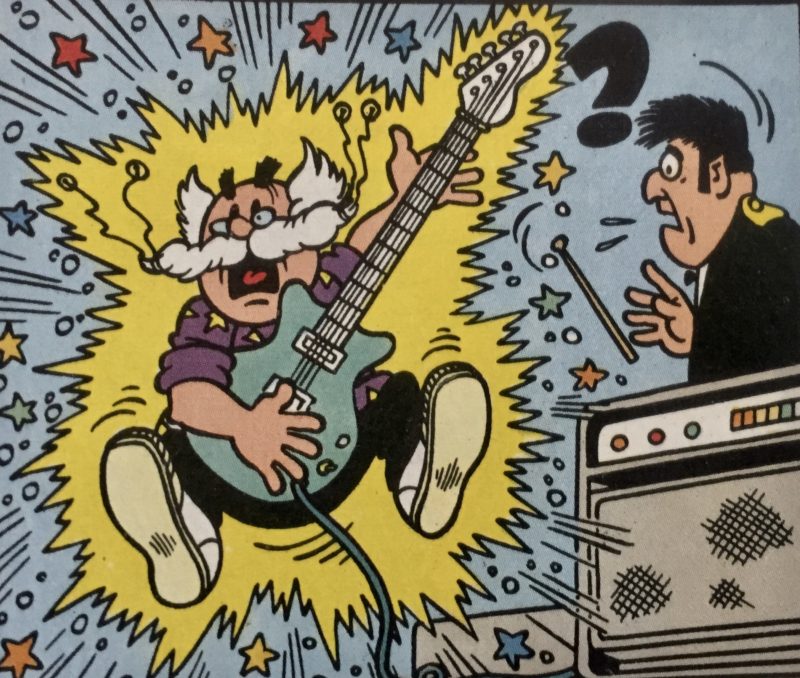

The contrast with Gobelijn could not be bigger. In Jommeke nr 269 'De Lawaai-eter' (The Noise Eater), Gobelijn introduces a decibelmeter as a giant ear on a stick. The louder the environment, the deeper a red the ear becomes. In a Cagean quest to find silence Jommeke and Filliberke take the ear for a walk but they fail wherever they are heading. When Gobelijn also invents a method to charge batteries with the vibrations of the human voice, he is convinced that because of him humankind now enters 'the era of sound'. Sound for Gobelijn apparently is nothing else than functional matter. In the story 'De Super Popzanger' (The Super Pop Singer) from 'Drie in een slag', nr.125, it is only because of some explosion and a hard hit on the head that Gobelijn really loses his mind and decides to become the world's most famous pop singer. As soon as he is electrocuted on stage, he changes his mind. Again, music is presented as a form of delusion, keeping Gobelijn back from his main cause, i.e. invention.

Gobelijn's delusion turns into Imagination in Vanhoof's art practice. The invention should always be an answer to the life improvement of the imagionationless masses. Central in today's experience of the world is the computer, the extended brain everyone loves to hate. As an answer to the macro-economic malaise and its subsequent psychological mass delusion, Vanhoof developed his latest set of installations 'De Vloeibare Computer', a visionary response to the question of how to free ourselves from the archaic concept of the computer, by reinventing the very idea we have of it. A product of an epiphany after having read a passage about the hydraulic computer in 'The Pattern on the Stone' by William D. Hillis, 'De Vloeibare Computer' guides the listener/spectator through a space, stuffed with giant geometric cardboard creatures, in which filtered digital noise fills the room. The noise comes from a rotating Leslie speaker which in a first version was combined with lamps providing the necessary flickering element Vanhoof is so fond of. In another installation, called 'Polyhedra', the same geometric forms are hanging from the ceiling in smaller sizes, all carrying different kinds of speakers. The installation plays with our idea of listening and sound. Vanhoof masters the deconstruction of both concepts and routines, but never in the idle or distant way that characterises a lot of postmodern art. That is what I have always considered his biggest strength. In his enthusiasm and playful approach of serious matter, he remains a Gaston-like version of Paul DeMarinis, a professor-artist who operates within but looks far beyond a contemporary art world.

Over the course of the past 15 years, I have seen many of Vanhoof's exhibitions and expanded cinema performances. I have seen him in living rooms, concert halls, artist squats, galleries and fancy museums. I have seen flicker films and heard sounds of his that will never leave my memory. An eternal teenager myself, I deeply relate to the The Inventor and Imagination as key concepts to discover Beauty and Solace. Vanhoof has been deliberately side-tracking those routes of Invention and Imagination to discover and develop ever new ways of looking and listening at things, and therefore making the world a better place.