guts magnet sea

Though there seems to be nothing (no body, no ground, no sky), a jaw bone aches and is stiff—a sensation felt, yet with no soul here to claim it. The jaw creeks open. Soured breath overwhelms a sinus passage, a pungent flavour causes gasping and, finally, a familiar feeling—in my chest—a kind of death. And once again I am staring at the ocean, listening to its waves, flicking at this metal reed between my teeth.

I drop the harp into the canvas pouch tied to my belt and peer through the fog. Nothing but fog. I stumble onward.

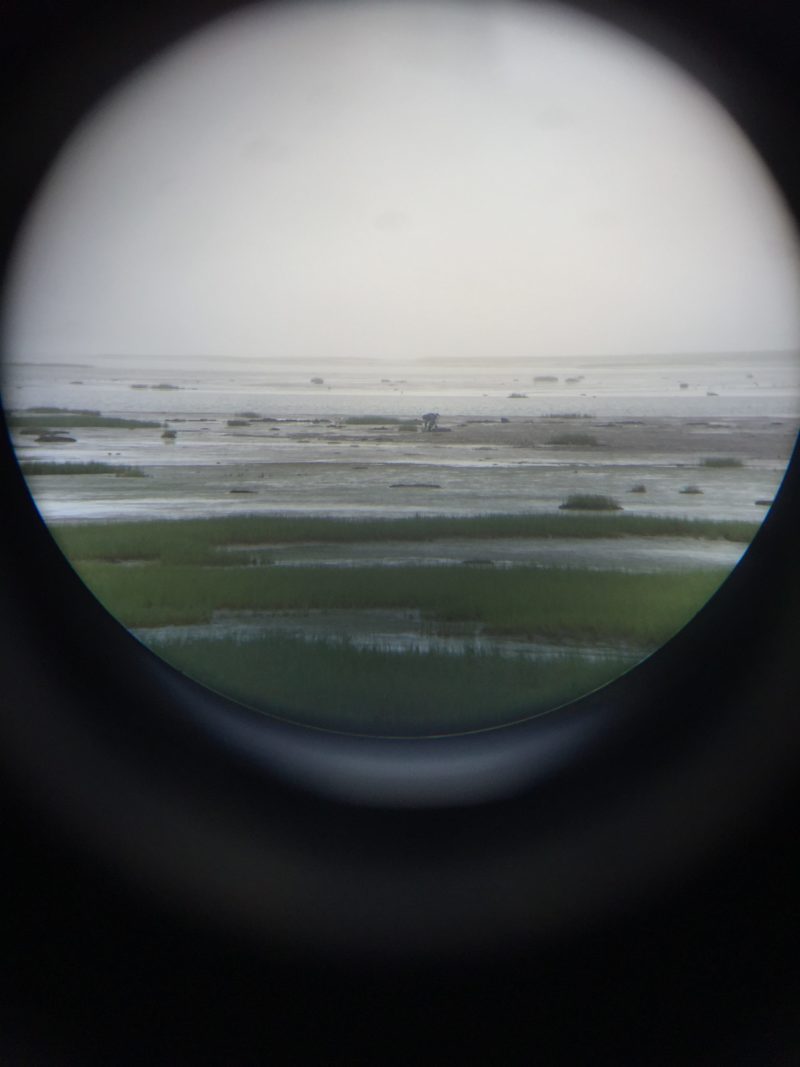

The islet I am searching for is just a clumpy ring of muddy banks, only about two stories high. Years ago I would hike there each day to play my jaw harps. But now this slab of earth is only accessible during the lowest point of an unusually low tide, an exceptional occurrence, at which time the half-kilometre-wide channel separating the islet from the main beach dries out. And that’s where I find myself now, carefully scurrying across a field of slimy, skull-sized rocks, the pouch of jaw harps at my waist swinging each time I slip and lose my balance. These rocks are not only hard to walk on; because of their black, salt-smoothed bodies, often with living seaweed and algae of various colours attached, they also play tricks on my vision.

In my peripheral, a dead seal. Bloated, her head chopped off clean, skin tucked into the collar of her gapping neck. I turn to her, she is gone. Just a stone. Raven wings, a bit of meat on the ends. But no body. White barnacles cling to the rock under my feet. They cut into my flesh and send a jolt of pain through my body.

Violent winds arise, erasing the fog. And finally I am able to see my islet in the distance—those muddy banks cower as waves, each one more monstrous than the last, crash into them. The roar of it all is fantastic—a deafening drone that mingles with my pounding heart’s beat. I continue across the channel.

A dead sculpin, its eyes eaten, boney face smiling. A fluorescent deck hand’s jacket, long ago lost at sea, rests in a mound of pebbles and periwinkles. A seagull skull with a fishhook in an empty eye socket. A human face looking up from beneath the sand? A deer hide. Waist-high hills of clamshells, crushed almost to powder. The smell takes my breath away. Eels, skinned and wrapped around the base of rocks I now hurry over. The winds are making it hard to stay upright.

And the tide is turning; there is water now lying on the sand at the base of these stones. My right foot is bleeding. I dip my toes into the salt water, hoping for relief, but the water burns like acid. I fall hard onto a cluster of stones, and in the process, my finest jaw harp—a hand-sized dagger of a harp— slips from my pouch and falls into the water, where, long after all jaws are gone, the salt from a million tides will erase every trace of its existence and mine. Tempted to play it one last time, I decide to move on before the water traps me.

Way down shore, far from here, a sublime tower of driftwood snakes into the sky; it grows fat on fallen trees from the islet in front of me. Even before this causeway washed away, back when the islet was a peninsula, I would see new victims—century-old evergreens pointed straight down the mud banks to the intertidal zone below, their roots exposed and turned upwards to the heavens. Their slide took months sometimes, so that when they finally arrived at the beach below, their flesh was already turning to stone. Here they’d wait for the next storm to drag them into the heart of the ocean, where they’d further merge with salt and sand. And just before being fully absorbed, these hapless trees, last witnesses to the land they once held, would be thrust back out of the depths to become one with their brethren, in that tower of petrifying wood. Today, the trees of the islet fall and are reborn in a rhythm that moves beyond time. All is dissolving.

Blankness has fallen and I am blind but for sound. The sea and the wind rage. The thunder of mud pouring into water. I have arrived. It must be so.

Despite the unrelenting noise that surrounds me, a distant, singular voice ensnares my remaining senses. Its piercing tone sends shockwaves through my bones and makes my head spin. Dizzy, I lie down and place my ear to the ground. Do I hear myself on the other side, under the ocean? As mud pours over my legs and water fills my lungs, I struggle to pull a jaw harp from my pouch.

What is it that I am doing with my mouth, with my throat, my lungs? It’s the most basic of all physical gestures. That hissing sound is just saliva being pushed into the back of my front teeth by my tongue. That sickly drone is echoing out of my lungs and diaphragm. I accentuate the sound of breath in my windpipe and call it music.

The metallic vibrations in my skull are set ablaze in these dreams of an infinite sea. But tonight the sea retreats.

I rise from the ground and shiver in the cold winds.