Songs of the Earth: Mesias Maiguashca

Mesías Maiguashca (Quito, 1938) is part of the first generation of South American maverick sound explorers that in the 1960s paved the way for a tradition of innovation that persists in the present noise and psychedelic scenes of the continent. Along with Edgar Valcárcel, César Bolaños, Beatriz Ferreyra, Mauricio Kagel or José Vicente Asuar, he contributed to expand the possibilities of musical language beyond the dominant Western canon and the rigidity of certain styles of national folklore. He will take part of the KRAAK Festival 2020 with a unique performance of his wooden sound sculptures for his composition Holz Arbeitet II.

Like a true native of Ecuador’s capital, Quito, Mesías Maiguashca comes from a distinctive neighbourhood with its particularities and traditions: the working class, mixed race district of San Diego. A son of indigenous intellectuals that were among the first to bring to Ecuador the ideas of progressive education, he learned to play the piano from an early age. This instrument came to his family as a payment for the legal services provided by his father, a lawyer of deep liberal beliefs that wrote a book on the condition and identity of the indigenous people of the Americas. From that point on, Maiguashca started on a persistent adventure in sound. At the beginning, it consisted of a formal Western classical education provided by the local conservatory and the popular Latin American songs that came out of speakers in the buzzing streets and bars of San Diego. He likes to say that his mind would have a pavlovian response to Bach, Debussy or Chopin, as it would immediately evoke the memory of a bolero, a tango or a pasillo. He vividly remembers how these songs would effortlessly crawl from outside of his parent’s house to the room where he rehearsed some solemn romantic tune.

Promptly, Maiguashca could continue his education at the Eastman School of Music, and from there he went on to study composition in the exploratory studios of the Instituto Torcuato di Tella in Buenos Aires. In 1966, he came to the WDR in Cologne, directed at the time by Karlheinz Stockhausen, whose influence was determinant in his work, encouraging his sense of freedom even more. From the 1970s onwards, Maiguashca followed a very personal path in which he tackled a wide range of registers and modalities of electronic music (subtractive synthesis, FM synthesis, computer compositions, concrete music), but unlike several of his European contemporaries, his work is characterised precisely by its combinatory adventurousness which involves chamber ensembles, organs, amplified wooden and metal objects.

Maiguashca’s creative journey is punctuated with pivotal moments of discovery and the acquiring of a deep sense of creative freedom. At the Quito conservatory his teachers maintained the belief that the likes of Beethoven or Schubert form an unsurpassed milestone and virtually forbade their students to compose, unless they created works that could compare to the great classics. Maiguashca rebelled and at his graduation piano concert played one of his own compositions, uncovering inadvertently the way to his own creative endeavour. At Eastman, Maiguashca went to a series of lectures by Henry Cowell who introduced him to the work of Anton Webern and talked about the new music that the conservative American elite still frowned upon at the time. Cowell impressed him when he played one of his own pieces, “The Tiger”, which with its unorthodox playing techniques (hitting the keyboard with fists and elbows) opened in Maiguashca’s spirit the possibilities of creating music independent of tonality that can include noise as its raw material. Eventually, in Cologne his personal research would completely open with the help of the almost infinite possibilities of an electronic music studio initiating a process of “an individual, necessary and compulsive research.”

The new possibilities of experimenting with electronics awakened in Maiguashca philosophical questions. The very physicality of sound motivated his research on acoustics as well as a growing fascination for the work of Alvin Lucier for their shared interest in sound spatialization. This period concluded in a series of pieces where space and movement helped to create tonal variations and immersive listening experiences (most notably in his Ton Geographie series). The deep commitment to abstraction recalls the Schopenhauerian conception of music as a reality in the absolute sense, where sound establishes its own material existence in a virtual reality. On the other hand, Maiguashca detached himself from the excesses of abstruse theorization by harboring the belief that his work is also an exercise of introspection, even asserting that all art is in a way a form of autobiography. Many of his works try to balance his personal life with an ongoing research into the nature of sound. Maiguashca’s iconic piece Ayayayay that evokes the streets of the San Diego district or Oeldorf 8 (soon to be reissued by the German imprint Karlrecords on LP) come to mind as they were conceived as sonic diaries with an edge to encompass radical electronic synthesis.

In the last thirty years Maiguashca went further into his personal story and expanded it to its ties with the indigenous origins of his family and the dramatic history of Ecuador. One of his most important works is the musical reading of the poem of the avant-garde poet and mystic César Dávila Andrade, Boletin y Elegía de las Mitas. It is a lament honouring the indigenous victims of the colonial rule that has lasted in its various forms for more than five centuries, imposing to the population enslaving and exhausting chores in mines and fields. This grave and lyrical text is also one of the first masterpieces in sound poetry in Latin American literature. Dávila lists quichua names and places while gradually displacing Spanish from the poem’s pages, transforming it into a faint echo. The sonic effect of these words pronounced slowly one after the other has certainly appealed to Maiguashca, who read Dávila under the influence of the political civil rights essays of his father. The result of his adaptation was considered by the Ecuadorian critics as a synthesis of Maiguashca’s work: it contained a great deal of his experiments while retaining an epic quality that strongly engaged local audiences.

Mesías Maiguashca remains very active today: he is currently preparing for another live instalment of his Canción de la tierra, which is another hybrid epic about his homeland that combines abstract electronic music, his current research in sound sculpture, dance and video performances that will premiere in Quito and Berlin this year.

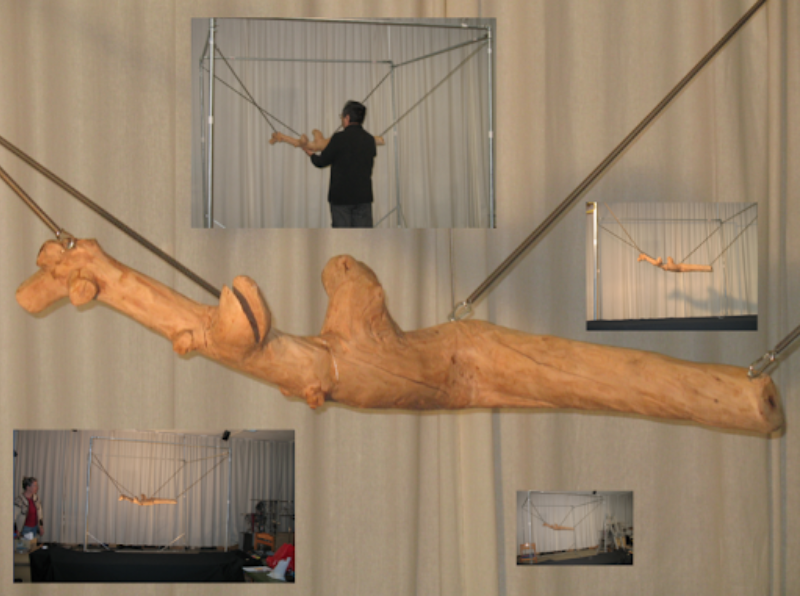

Regarding his participation at KRAAK festival he will propose a performance of his piece Holz Arbeitet II (2005, for wooden sound objects, two performers and electronics). In our exchanges in preparation for this article, Maiguashca stated: “This piece represents well many of my musical concerns. The sound source consists of rustic wooden sound objects amplified by contact microphones and played by two performers, with the help of bows and mallets. The traditional harmonic musical world consists of precise pitches, grouped in scales that allow traditional musical notation. The sound world of a ‘sound object’ is, on the contrary, a world of inharmonic sounds close to noise. A conventional notation is not possible. In this work, it is not the sounds that are heard that are noted, but rather how they are produced: it is an action notation. Musically, it is an improvisation controlled by a score. You can make as many versions of it as you wish. Normally, I have been using electronic transformations when I use sound objects, as I have not wished to ‘degrade’ the quality of the original sounds, which seem to me, as they are, fresh and interesting. However, in this work, I use two vocoders (electronic modules with two inputs - ‘audio’ and ‘control’- in which the spectral ‘control’ information is printed on the ‘audio’ information). The ‘control’ signal is that of the interpreters, the ‘audio’ signal is a recording (made by me around the 1980s) of religious chants in a Holy Week procession in Quito. In the beginning of the work, only the sounds of the wooden objects are heard, then the interaction of them with the recorded music, and finally only this one, controlled by the spectral information of the music made with the wooden sculptures: in a way, the pieces of wood start ‘singing’, so to speak, the religious songs.”

Mesias Maiguashca will conduct a performance of Holz Alberteit II, Saturday 29.02 at KRAAK Festival 2020. Beware, it's quite short - be on time if you want to witness this awe-inspiring piece! Get your festival tickets here.