The Circularity of Razen

Niels Latomme

Let’s start with the title of the new record.

Kim Delcour

We borrowed it from the book Memoirs, Dreams, Reflections by psychologist and anthropologist CG Jung.

Brecht Ameel

Jung visited a village in Kenya, on the border between Kenya and Rwanda. While there, he studied a different concept of time and a different position of man in relation to nature.

KD

He saw a corpse on the street in the village. The villagers stood around it, dripping milk while reciting the words Ayîk Adhîsta, Adhîsta Ayîk. Freely translated, these words mean He came, he’s gone; or he goes to the good, he came from the bad — or the other way round. Crucial is the circularity.

BA

It can also be translated as from day to night, from night to day.

KD

Adhîsta refers to the normal, the daily, the rational, while Ayîk refers to the unseen, the dark, the night. The spell enhances a cycle. Jung noticed that the villagers would go on the roof at dawn, spit in their hands and, with their hands, they followed the movement of the Sun. The Laidon, the elder, told him that it had always been that way. Within his theories of the collective unconscious, he explained the ritual as a way to help the Sun. For the villagers, they had no right to be in the night. It’s another world that belongs to demons, spirits and other creatures. People have to stay inside, and they feel responsible for the return of the day.

BA

Imagine the fear every night, not sure that the day will return. This fear is an important part of our new record.

KD

The record starts at dusk. At the end of the first side, the subject enters a state of death...

BA

… or at least a state of in-between, a state of non-being.

KD

The second side of the record represents the movement from this non-state towards life. It’s a circular record: from day to night, from night to day; from light to dark, from dark to light; from the rational to the irrational, from the irrational to the rational… This ritual and its presupposition of a shadow world was very important in the theories of Jung: he believed that the conscious is just a tiny part of a man, and that the unseen, the dark, the unconscious, plays a far more important role.

BA

The night is an archetype. Archetypical sounds are very important for Razen — not to evoke the defined, the conscious and the rational; on the contrary, we use sounds to evoke the in-between, the shadow and the irrational. That’s probably why we came in contact with the writings of Jung and the Ayîk Adhîsta ritual. I see a lot of beauty in his research: as a rational scientist he wanted to understand the human mind, but he realized that he had to enter the terrain of the unscientific. The irrational became the key to explain and understand the human psyche. His theories and work are injected by the idea that the unconscious is part of nature, and is real — it doesn’t lie. A dream is maybe hard to explain, but it’s not fake. He entered our domain, art, where we explore the irrational...

KD

… or the religious, or even pre-religious. At least, the spiritual.

NL

Jung had a couple of childhood experiences that defined his research and thinking. One of them was the fact that as a kid he had a small box with some relics. Later he discovered that non-Western cultures had similar objects and rituals, which led him to the theory of the collective unconscious — new, compared to Freud’s theories. I’m not so interested in the cliché of how certain traumas defined you as grown-ups; rather, I wondered if you had similar childhood experiences which tune in to your current musical practice.

KD

I never thought about that.

NL

Maybe I should rephrase the question: is it relevant to relate certain characteristics of your musical practice to your childhood (like Freud would)?

BA

Yes and no. It’s very relevant to question how the past defines the present. We both are very open to this sort of information. In your life you meet certain people — teachers, parents, older friends, whatever — who give you certain directions, like maps. Jung wanted to draw a full picture of reality, even if that meant throwing away the map of the rational/scientific and go out there in the dark. Jung, like us with our music, and certainly the new record, threw away the map to access full reality, or at least to other and/or possible realities.

NL

Then it’s quite remarkable that the new album sounds more ‘classical’: it evokes a whole array of recognisable ‘human’ emotions — fear, anxiousness and melancholy, which is a more common terrain in conventional music. For Razen, though, it’s new: previous records evoke a dehumanized, transcendental vibe, exploring undefined, unfelt and new emotions.

KD

The pieces are defined by the space. As you know, crucial for Razen is respect for the space: it acts like an extra musician. The church where we recorded this album is different from the other churches. It was built in the 20th century, and doesn’t have the classic elongated ground plan. It’s more square, and much bigger.

BA

The organ was placed as such that I had direct visual contact with the other musicians. We also played in a new way, although it’s hard to explain why. On most of the pieces there’s only two or three of us playing at the same time. There are almost no sustained tones. And I had the impression that the echo was longer than on previous church sessions.

KD

There was no starting point or defined idea either. Normally we always prepare some rough musical ideas. I remember that this time we used the metaphor of a raffled string or cord, which we had to stretch very carefully without breaking it. It was a matter of using a minimum of words, finding the breaking point where a sentence almost implodes.

NL

On previous records Razen sounds like an ensemble of nightly spirits, dehumanized presences that are out there, whereas on the new record, Razen sounds like a human individual, occupied with its human, individual and inner emotions. It feels as if there’s a shift in your point of view – more subject than object?

BA

It’s indeed a very human record, appealing to a very human fear that the night won’t stop.

KD

Fear of the dark is an archetype in itself. We were surprised ourselves that the pieces sound so emotional. A lot has to do with the fact that we recorded in the evening and at night. Sounds sometimes change at night, and this influenced our overall sound.

BA

On previous records we had a more abstract and detached approach to our playing. For this record the emotional engagement is stronger, in the way each tone is played, and in the accentuation. On previous pieces, each tone just kicked the door in.

KD

The sounds are more fragile and vulnerable. Even more than before, we listened very closely to each other. Although we did record a lot of pieces that were typically old school Razen. We didn’t select them, because they didn’t fit into the general idea of Ayîk Adhîsta.

NL

So, there was a concept before you started recording?

KD

Not really, it was maybe in the air, but the idea popped while selecting the tracks for the record.

NL

Is this a new step as a collective?

BA

Not really a step, but a new possibility. The record is not made by a group of soloists, the group is still the instrument.

NL

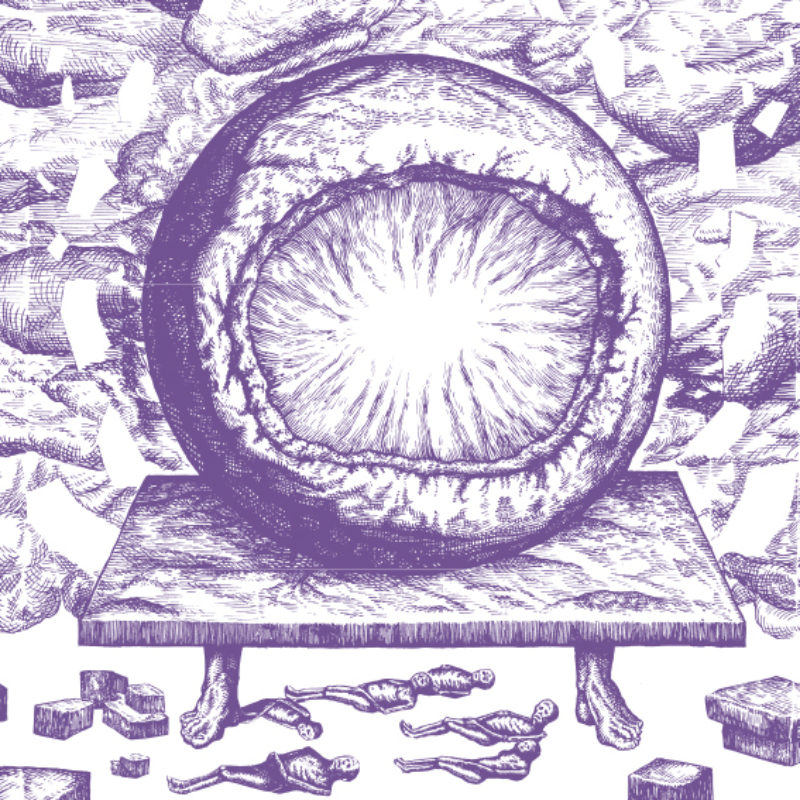

The story behind the record is quite explicit — partly due to the design — compared to your previous records, where there is simply an image and dry liner notes.

BA

We don’t see the difference, because every album has a story. Maybe it felt more natural to give an indication this time because people can relate to it more easily.

KD

Originally we wanted to add a time indication for each track, so that it becomes clear which track reflects which moment in the night. But that would have been too explicit.

BA

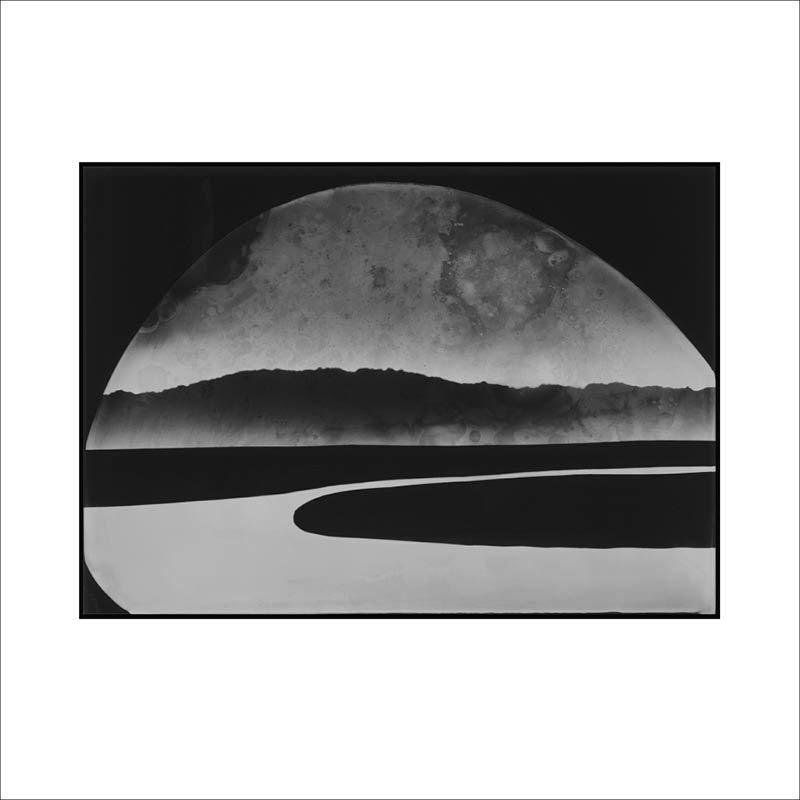

Also the photo we used for the front cover is almost a direct visualization. It’s a road, a metaphor for the journey through the night, or it’s a river that you’d have to cross, or it visualizes unknown territory, where the map you’ve got becomes useless. Or it could represent the night, which brings us back to the ritual...

NL

Your music has a very instantaneous character: it drives on the ‘now’. The way the pieces materialize during sessions and the almost ritualistic concerts tend to force people into a mental space where they experience the ‘now’ in a very direct way, which is a feature of a lot of so-called minimalist music. But since the invention of tape, a record has a historical character: as an object, it’s always released weeks or months after the event when the music happened, and it registers the music into some sort of musical history, taking its position alongside other records. Isn’t this a paradox?

BA

Yes, sometimes it’s a bit difficult. On the other hand, we don’t obey the rules of the music industry, where we are supposed to reproduce the songs of the albums on live shows. It’s sometimes a pity that there’s so much time between the recording and the release of a record, but you have to accept it.

NL

Could you say that a record and a concert are two entities of Razen?

BA

For sure. The goal is a Sun Ra-like discography, putting our own ‘cosmic newspaper’ out there, and apart from that great live concerts.

NL

So Razen will go on for a while, if you aim for the same amount of records?

KD

In this life and with good health… Absolutely, this path…

BA

… feels so natural.

KD

When Brecht showed me this picture from our first concert at Les Ateliers Claus, I was a bit shocked actually. Not by the fact that we aged a little (laughs), but by the fact that it’s already ten years old.

BA

It surely doesn’t feel like ten years, probably because the way Razen works feels very close to who I am as a human.